When Grief Meanders: A Lament for My Sister

When Janae got embarrassed, things got funny. Like when she lived in the apartment above us, and she needed help with her luggage. I don’t remember where she was returning from–we were both working with a missions agency, and she traveled often–but I remember it was a short trip. Far too short to necessitate a suitcase with the approximate weight of an upright piano. I laughed all the way up the stairs, making the usual comments about anvils or corpses, and she launched into her embarrassed defense.

“What? It’s not that heavy!” But it was, and she knew it was, and the more red-faced she got, the more words came out. She needed those cute shoes for her green outfit, didn’t she? And what if got cold? She would need that thick coat if it got cold, and then she would need her boots! Janae’s packing tendencies were only matched by her blushing verbocity: less was never more; only more was more.

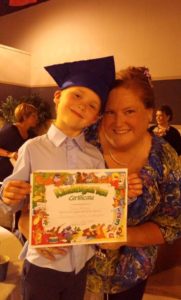

That was my sister. We had different parents, but for the past 16 years, Janae Alice McWilliams was a staple in the Hague household. She was a part of us. When we left Texas for California, we left together. When we migrated from California to Oregon, we migrated together. When we lost our dear Karen, we mourned together in the little house we shared for more than three years. She was my kids’ auntie and chief cheerleader; their personal, in-home Mary Poppins. She went to dance recitals and soccer games, and when Sara and I couldn’t make one of those events, we never worried too much. Janae could be there. That would be plenty for the kids.

That was my sister. We had different parents, but for the past 16 years, Janae Alice McWilliams was a staple in the Hague household. She was a part of us. When we left Texas for California, we left together. When we migrated from California to Oregon, we migrated together. When we lost our dear Karen, we mourned together in the little house we shared for more than three years. She was my kids’ auntie and chief cheerleader; their personal, in-home Mary Poppins. She went to dance recitals and soccer games, and when Sara and I couldn’t make one of those events, we never worried too much. Janae could be there. That would be plenty for the kids.

But she can’t be there anymore. Janae left us five weeks ago. It was cancer. At her memorial, everyone talked about how extravagant she was in the way she loved people. With the possible exception of her mother, I think Sara and I received more of that extravagance than anyone else. It started the day Jenna was born, nearly 16 years ago. We were supposed to be moving into a new place that day when Sara’s water broke, and we had to abandon the moving team we had already assembled. Janae took charge of them all, so that when my wife and I came to our apartment with baby in arm, there were no boxes to unpack. Beds were set up, the crib assembled, and everything was in its place. Even our clock was on the wall. There was something about that clock. When we saw it, we both cried at the great gift our friend had given us.

That was when it began. That was when we knew she would be ours.

Janae’s over-the-top tendencies always drew a sharp contrast to my  own absent-minded minimalism. Truly, she was my sister, but we could never have grown up in the same household. Her grand gestures always dwarfed my own feeble attempts at appreciation. She gave the best, most thoughtful birthday presents. I gave her gift cards. That kind of thing always embarrassed me, but how could I compete with her? How could anyone compete with her?

own absent-minded minimalism. Truly, she was my sister, but we could never have grown up in the same household. Her grand gestures always dwarfed my own feeble attempts at appreciation. She gave the best, most thoughtful birthday presents. I gave her gift cards. That kind of thing always embarrassed me, but how could I compete with her? How could anyone compete with her?

“JasonHague, are you at the office?” That’s what she called me. She rammed my name together until it was one syllable.

“Yeah, why?”

“Good. I have a surprise for you. I’ll be there in a minute.”

And then she’d come with a latte or a CD or a Toblerone, and I’d feel embarrassed again, because after so many years, the tally of gifts was heavily in her favor already.

I’m not sure she noticed, though, because really, she did this with everyone. She loved to figure out people’s favorite things so she could tell them, “I have a surprise for you.” When she gave the gift, she’d pounce on them with a gigantic hug (she is famous in seventeen nations for her hugs), and an exuberant monologue of unbridled encouragement would ensue.

That was my sister. She loved people with candy bars and  wild words of praise; with long conversations, deep embraces, and clocks on the wall. She spoke all five love languages with a native accent.

wild words of praise; with long conversations, deep embraces, and clocks on the wall. She spoke all five love languages with a native accent.

My kids have learned much from her. “Miss Janae, you make my heart smile,” Sam would tell her as a four year old, because that’s the way she talked, and he wanted to speak her dialect. I tried it, too, now and again. She loved Cherry Pepsi, and when I dropped by her office, I’d occasionally bring her one.

“JasonHague, you’re just the best!” she would say, and pull me in. I’m not much of a hugger. Everyone knows that. She knew that, but she didn’t care. Because she could see through my relative minimalism. She knew I loved her back.

And now that she’s gone, that’s what I’m counting on. That she really knew. Because like all brothers and sisters, we butted heads all the time. We knew each other too well.

When I turned forty in November, my friends had one of those mandatory, “say something nice about Jason” circles, and she pounced.

“JasonHague, you are my favorite,” she said. “And that’s what I tell people: JasonHague is my favorite.  But sometimes, he can be such a jackass!” We all fell apart laughing. It was perfect. But it also stung just a tad. Not because she was wrong; I know full well that I can be a jackass, and I didn’t mind her saying so. No, it stung because of where my mind flashed to; the times I hurt her like almost nobody else could. Like when I took her for granted, as if her die-hard devotion to me and my family was somehow pedestrian; as if it was a small thing to hear people gape at how much she loved us; as if her unassailable, self-sacrificial loyalty to the Hague clan was our right, and not her gift.

But sometimes, he can be such a jackass!” We all fell apart laughing. It was perfect. But it also stung just a tad. Not because she was wrong; I know full well that I can be a jackass, and I didn’t mind her saying so. No, it stung because of where my mind flashed to; the times I hurt her like almost nobody else could. Like when I took her for granted, as if her die-hard devotion to me and my family was somehow pedestrian; as if it was a small thing to hear people gape at how much she loved us; as if her unassailable, self-sacrificial loyalty to the Hague clan was our right, and not her gift.

I still wince, even though I begged her forgiveness, and she gave it freely. I wince, because I fear she died with my small bruises still on her soul.

Last week, I was with a group of friends at the coast, trying to be social. It’s harder than normal. Everything is harder than normal right now. Janae’s health declined so rapidly that her death feels more like a sudden accident than a lost cancer battle. We didn’t have time to brace ourselves, and even a month later, the tears come suddenly and won’t stop. Even in the coffee shop where I write this right now, I can’t quite turn them off.

I said in my book that grief doesn’t walk in a straight line, but that it meanders. I’m now remembering how right I was. It doesn’t matter that I’ve been through this before. Mourning is still an expedition, and I’m not leading it.

On Saturday at midnight, I sat on a cliffside bench staring at the dark Pacific waves raging beneath me. The coast is usually my happiest, most peaceful place; the spot where words flow freely, and glimpses of God’s eternal presence come unbidden. But they didn’t come that night. Instead, my minimalism got the best of me. I didn’t even have a coat to shield me from the cold Oregon wind. In this way, like so many others, I was the opposite of Janae. I always try to stuff only the essentials in my backpack. It’s a matter of pride: I don’t need much. Less is more.

But sometimes less is just less. I had to wrap myself in a blanket from the house, because the world was cold, and I missed her.

God was up there, of course, hovering over the face of the waters, but I hadn’t packed any prayers for him. There was just not enough room in my bag. So I looked up at the clouds and said only one thing aloud: “Can you just sit with me tonight?” Because those were all the words I had. And I think He honored them.

“Love covers a multitude of sins,” St. Peter said. I believe him. I think God sees me down here in my brokenness, and sits with me in the silence. He sees my questions and brewing resentments, but He has enough love to cover it all. In my deepest places, I know His love is enough. I know His goodness is intact.

But does Peter’s statement extends beyond God alone? To Janae herself, I mean? I can only hope, because that’s all I have left. I can only hope that what she told me in the hospital was true: that I had helped to heal her heart. That sixteen years ago, she had needed a brother in her life, and God had given me to her. That I–that we–had been every bit the gift to her as she was to us.

Hope is all that’s left, because she’s gone now, and it’s too late for more Cherry Pepsi. It’s too late to double check whether I displayed enough of my overly-casual love to make her more or less forget my times of jackassery.

I know they say not to have regrets, but I have them. I think it’s okay to look back and wince every now and again; to hope that our love was wide enough, and to trust that even where it wore thin, things might still be okay. Because whether we pack heavy or pack light, this life is a temporary destination. Eventually, we will go home, and Someone else will have to carry us up the stairs. We will have to trust that His love is full enough to make up for all the places ours wore thin.

know they say not to have regrets, but I have them. I think it’s okay to look back and wince every now and again; to hope that our love was wide enough, and to trust that even where it wore thin, things might still be okay. Because whether we pack heavy or pack light, this life is a temporary destination. Eventually, we will go home, and Someone else will have to carry us up the stairs. We will have to trust that His love is full enough to make up for all the places ours wore thin.

Every night at bedtime, Nathan, my seven year old, has been praying the same thing: “Jesus, please tell Miss Janae that we love her so, so, so, so, so, so much.” I don’t know if his theology checks out, but it’s a good prayer. And today, it is my prayer, too: that the one who loved with such extravagance might understand, today, how much we loved her, too.

(We took this video this past Christmas day. I’m so glad we did.)