All birthdays are special, but some are more special than others. The sixteenth birthday is one of the very best ones, because when you turn sixteen, you’re almost done being a kid. And on days like this, a lot of people start to think more about what they might be able to give to the world in order to make it a better place.

I know you see these things in your siblings: Nathan singing and dancing on stage; Sam making everyone laugh with his impressions; Jenna creating amazing artwork; Emily making beautiful things out of words. These are all gifts, kind of like in Encanto.

Son, you don’t talk very much, but you have gifts, too. Maybe you think you’re like Mirabel in the movie, who didn’t get one. But Mirabel was wrong, because she did have gifts. She had the gift of seeing and understanding other people. That’s how she was able to bring healing to her family. Some gifts aren’t as obvious as others.

You have some obvious gifts that everyone sees. You have joy, for one thing. People see you skipping through the hallways on Sunday mornings with Leeli on her leash, and they smile, because you’re smiling. Your joy spreads.

But there’s something else, son—a surprising gift that we’re starting to see from you, and we want you to see it, too: Jackson, you are a storyteller.

Let me tell you why I think this is true. Stories are not just about the characters in the book or on the screen. No, they are really about how those characters connect with us, the people who are watching and reading. They wake up the sleepy parts of our hearts. You seem to understand this in a very special way.

Let me give you an example. Remember a few weeks ago when we were texting about Kung Fu Panda? You said to me, “You are Monkey because you are funny and I am Po because I am kind.”

This made me very happy for two reasons. First, you understood that you are kind. You see that in yourself, and that is a wonderful thing. It’s another of your gifts, just like joy. But you also recognized what the movie is really about. It’s not just about Po learning Kung Fu. It’s about how he had a good heart, even when nobody believed in him.

Do you see what I mean? Stories are about connection. The more I think about this idea, the more I suspect you’ve always understood it. Like when you related to The Good Dinosaur’s constant anxiety, or when you saw yourself in Mater, not just because he was awkward and you felt awkward, but because he was a hero, and you wanted to be one, too.

Yes, I think you’ve always understood stories. That should be no surprise, because we are a story family. It’s my favorite piece of our little home culture. But I think you can make them, too.

Last month, you were doing school work with mom. Your assignment was to use your communication device to tell us all about your favorite place, and to refer to all five of your senses. Here’s what you told us:

“I like going to the beach. I feel nice because I can feel sun and wind on my face. I like to listen to the waves crash on the shore. I like to watch the waves chase each other across the sand. I can smell fish in the air. I can taste the salt in the air, too. I like going to the beach with my favorite people, my family.”

I read that part about the waves chasing each other, and I shook my head in wonder. This is a poem, son. A story poem. As Hiccup said to Toothless, “You never cease to amaze me, bud.”

Jack, every time you put your thoughts into words like this, you help us connect with you. You bring us into your world so we can know you better. And we love getting to know you better.

You are turning sixteen today, son. You might not be like other adults-in-training, with all their talking and driving and thinking about college. That’s okay with us. But please believe me when I say that you have special gifts to give to the world. We need your joy. We need your kindness. And we need your deep and surprising sense of connection.

Mom and I love you, son. And we are so proud of the story you’ve begun to write. Happy 16th birthday.

Dad

]]>On this day one year ago, your mom and I put you into a hospital gown, and you let us do it. You knew what was coming. We had talked about it for weeks. Then, a nurse came and poked you, and you got sleepy. They wheeled you into another room, and when you got anxious, they read your list of movie titles until you relaxed and sleep came. And for the next weeks, you endured weakness and funny medicine and strange dreams and mystery pains in the back of your head. You didn’t like any of it, but you endured.

It was a strange few months after that. Do you remember the panic attacks that came every night? Do you remember when we moved your brothers out of your room so they could sleep? We may never know if that happened because of your surgery, or if it was an autism thing or something else. But what we do know is this: you made it through that dark season. You emerged, and you showed us the things that make you brave.

People have lots of funny ideas about courage these days. You see it in some of the movies you watch. One idea goes like this: “Courage is having the strength to be who you really are.” And this sounds good to us, because sometimes we all get embarrassed over things that are really just fine. Like when you flap your socks. Some people might not like when you do that, but you don’t care much, and I’m glad you don’t care. You shouldn’t have to care. You should be free to be yourself.

But I don’t think courage is like that most of the time. In fact, most of the time, being ourselves is pretty easy. We know our favorite movies and our favorite foods. We know whether we want to go to parties, or to hang out with our brothers and sisters. We don’t need to be brave to choose those things. We just have to do what’s most comfortable.

Maybe you didn’t think you were brave at all this past year. Remember in those really hard days when you would scream, “I ain’t a coward!” like Arlo in The Good Dinosaur? Maybe you thought that because you were afraid at night, you didn’t have any courage. But you did. You know how I know? Because ever since those dark days, you have have been making so many hard choices. And it’s been awesome to watch.

For example, remember those days last summer, when Mom and miss Beth took you to the bowling alley, to the movie theater, and the mini-golf place? You didn’t want to do those things at first because you really love just being home with your shirt off and your movies on. But your siblings stay home all the time so you can do those things, and this summer, they wanted to go have more adventures. So you chose to go out. And that was a good choice, son. You even started to enjoy yourself.

On one of those outings, mom took you to the trampoline park. Before your surgery, you’d had such a hard time using the left side of your body. But over the months, you had worked hard in OT until you were able to do this. It wasn’t your first choice. It would have been easier to say “no-fank-you” and do what was comfortable. But you made the better choice.

Later that month, we told you we were going on a family vacation. You said no at first. We never go on family vacations, because you like to stay home and relax in the living room. But you relented, and off we went, up the Oregon coast and down the cabin ramp on your scooter. You missed home, but you had a great time.

You also started to enjoy riding lessons more. Friday afternoons are a great time to come home and sit in your favorite chair for hours on end, but every week, you donned your boots and sunglasses and learned to cantor like Cowboy Pete himself. Just look at you go!

Finally, last week, Miss Janae took us to that place with all the Christmas lights. When we approached the “snowless tubing” slide, you kept eying it from around the corner. Your said nothing, but your face said, “Wow, that looks scary, but I really want to try it.” When it was your turn, you almost backed out. Almost. But then, this… You went again and again, laughing all the way.

And there is more, son. So much more. There were baseball games and hikes up mountain ridges and happy trips to the Safeway. You even sat through an entire live musical, Elf Jr, to see your little brother play the part of Michael!

These are the things that make us brave: not that we do what we want to do, but that we do the hard things we are afraid of doing. This is what you did this past year. Instead of settling for just “being yourself,” you sacrificed what you wanted for the sake of others. Instead of doing the comfortable thing, you chose to grow.

Well done, son. I’m proud of you. And I’m humbled by all the things you continue to teach us.

Dad

Like this post? Check out my book, Aching Joy: Following God through the Land of Unanswered Prayer

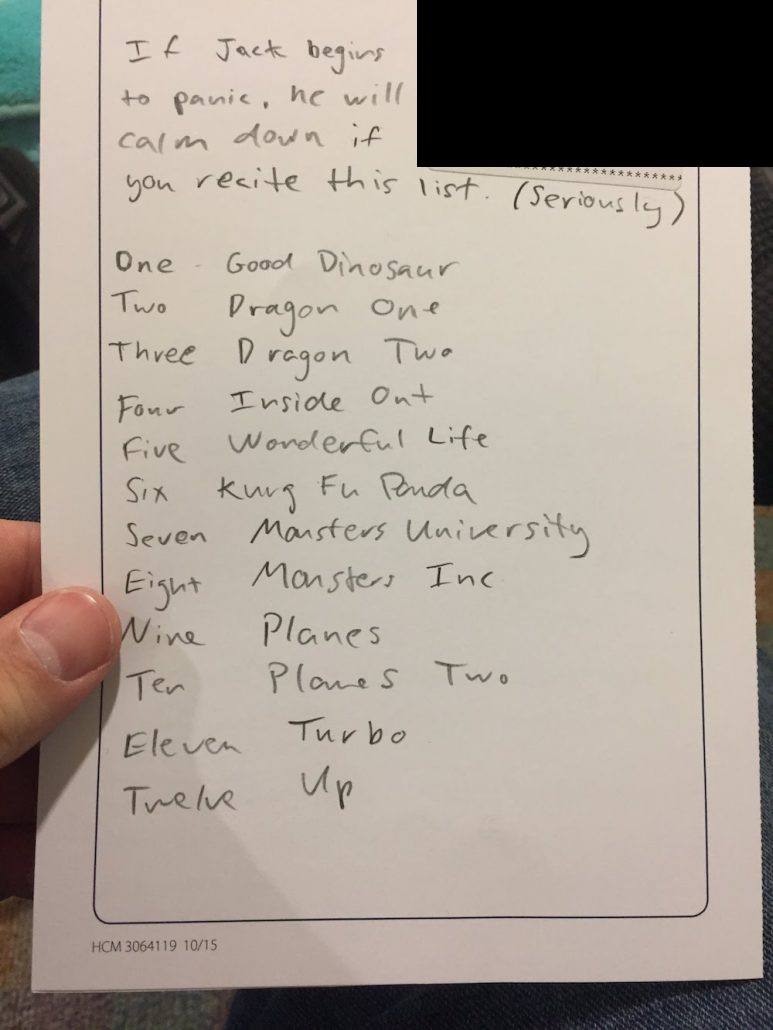

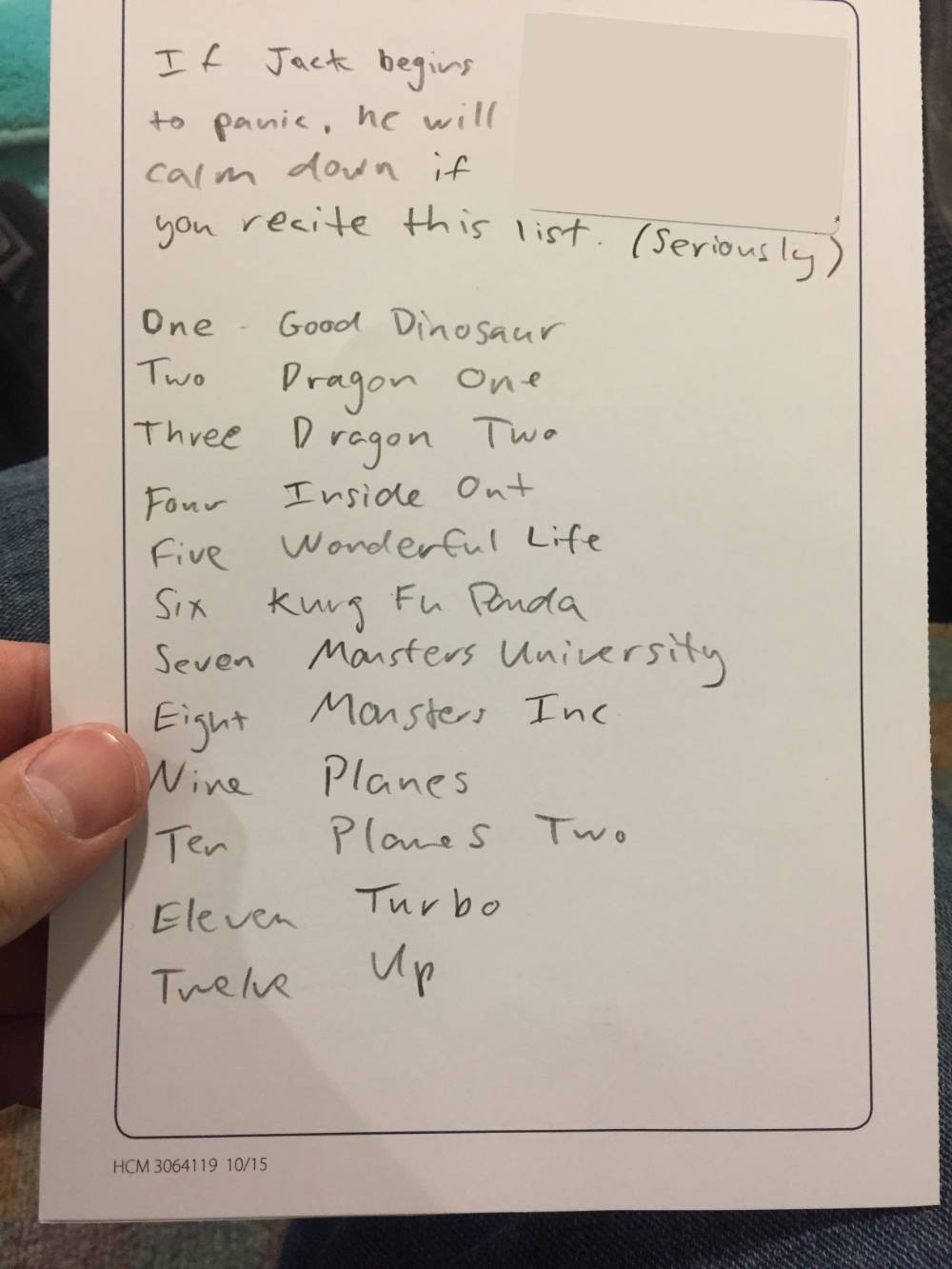

“One Good Dinosaur?

“Yes, Jack, one is Good Dinosaur. Now let go of me, and go to sleep. Please!”

[Pause.]

“One Good Dinosaur?”

This movie list was something of a revelation a couple months ago. It was a haven for him; a shield of comforting words to deflect the unpredictable world around him. But he’s become dependent on that shield. Now, if he doesn’t hear his words the instant he demands them, he panics. And he wants to hear that repetition at all hours of the day and night.

Thus, the past weeks have been frustrating for my young sons who share a room with him. They have to feed him his lines or else put up with the screeching every evening. It’s been demoralizing for my girls, who often have to take care of him and keep him calm when we’re gone. It’s been exhausting for Sara and I, because we lose hours of sleep trying to console him. And it’s been maddening for Jack, too. He’s probably wondering why he can’t seem to calm down.

We’ve been through some ups and downs with our boy, but I’m not sure we’ve ever seen such unrelenting anxiety. Not for this long, anyway. We’ve never dealt with so much panic.

So what’s going on with him? We don’t know.

He’s twelve, which means he’s got new hormones beginning to pulse through his veins (don’t try and make me say the word, YOU’RE NOT MY MOM!). He also had brain surgery two months ago, and who really knows how much that might be throwing him for a loop?

We ‘re working with some good professionals, and we are all on the case together. Please understand, I haven’t come here today for medical advice, or (God forbid) for pity. We are trusting our doctors, and we’re trusting God. We’ll get through this spell. We always do.

So why am I bothering to tell you all this? Because it’s true, that’s why. And because late on, when I tell you about the good times, I want you to be able to trust me. Parenting any child, let alone one dealing with severe autism, can be a heavy task. It is beautiful. It is also, at times, terribly difficult.

What good is it, then, to pretend life is binary?

The Twitter Tragedians who trumpet despair are every bit as half-blind as the the happy-clappy Christians who pretend to be “inside-outside-upside-downside happy all the time.” Life is not one dimensional; it is full of tension. The rain falls on the just and the unjust alike. Sometimes it’s an Oregon rain: light and drizzly, with no need for an umbrella. And other times it’s a good, old fashioned Texas downpour, and you get soaked.

We’re pretty drenched right now. That’s just the truth. But we’re not hanging our heads, because we know the clouds will part. We’ve already seen bursts of sunlight, like when Emily, our sixteen year-old daughter, discovered a new coping mechanism for Jack’s meltdowns. It happened last week during an awful panic attack. It was a bad one, and she was barely hanging on herself.

He ran into the living room, screaming at the top of his lungs, “One good dinosaur!”

He ran into the living room, screaming at the top of his lungs, “One good dinosaur!”

She caught him and wrapped her arms around him, whispering, “Deep breath.”

He listened to her. He inhaled, then blew out slowly.

“Good,” she said. “What’s next?”

“Two Dragon One!” he cried.

“Deep breath.” He obeyed again. “Good. What’s next?”

“Three Dragon Two!”

“Deep Breath…”

And on she went, all the way to “Fourteen, Up.” (Yes, we added a couple and we’re up to fourteen now, for those keeping score at home.) When she was done, he was calm again.

It was magic. My kids are magic.

So even though I won’t pretend that life is all breakfast peaches and unicorns on a Thomas Kinkade cobblestone porch, I won’t despair, either. We have hope. We’ll find a way. We’ll make it through this.

You’ll make it through your rough patch, too. The first step is to admit where you actually are. Acknowledge the anxiety. Acknowledge the pain. Pray from that place–that throbbing, sore spot. All the best prayers come from there.

And then?

Take a deep breath. You’re going to make it.

]]>You’re turning twelve today, and that brings me all kinds of feelings. It brings happiness, because you’re growing taller and stronger; not as cute but more handsome. It brings sadness, for all the same reasons. And it brings fear, because we have lots of questions about your future. Last month, though, you showed me something that made me a little less afraid.

Remember your hospital visit in January? Of course you do. It was a pretty big deal. You had a messed up blood vessel that was pushing up against your brain, and that was restricting the movements of your muscles. Over the past year, you had stopped running and riding your bike, stopped writing on paper, and your mouth had stopped forming some of the words you used to say. We think it was all the blood vessel’s fault.

After the doctor told us you should have surgery or else risk losing more muscle control, your mom and I didn’t want to talk about it very much. “Brain” and “surgery” are two very uncomfortable words when you put them together. But you needed to know about it, so we told you plainly what was going to happen. We told you we were taking you to the big hospital in Portland. We said that they would put you to sleep while they cut the back of your head open to fix a problem. And while we told you, you sat in silence, taking it all in.

That’s what you do. You take things in.

You know, son, when you were little, I didn’t try to talk to you very much at all. I didn’t think you were really listening. Mom would talk to you all the time, and I thought she was being silly. I thought she was fooling herself into believing you were able to do more things than you really could. Grown-ups call that denial.

But I was wrong. Mom wasn’t in denial. I was just afraid to believe that you might, in fact, be a lot more capable than I had given you credit for; afraid to think you might tougher and more resilient than I ever expected. I didn’t want to believe those things, because I thought I might find out I was wrong.

Eventually, though, I got over that, and we all started talking to you as if you understood everything. And when we told you about the surgery, I know you heard us. I know because after we opened all of our Christmas presents, you surprised us with three words, clear and perfect: “Go to Portland?” It was a week before the surgery date, but there you were, ready to charge in.

Son, you know in The Good Dinosaur, how Arlo is anxious about everything, and his dad has to tell him, “You’ve got to face your fears”? I think when you watch that part, you think the dad is talking to you. But that’s backwards. You always face your fears, son. If anything, it’s your father who still needs help facing his own.

The fact is, you are one of the bravest people I’ve ever met.

When I was twelve (or was it thirteen?), I visited a foreign country called Romania, where the culture was different, and the language was different, and nobody understood anything I was saying. It was fun, but it was also hard and sometimes confusing.

Is this what it feels like for you all the time? The world around you must seem so strange. You live in a culture that is hard to understand. We laugh so loudly, and we talk so quickly, but we aren’t very good at waiting to listen. You must live your whole life feeling like a foreigner. An outsider.

And yet, you walk toward it. You get through it. You march in like you did at the hospital, and you face your fears like a dinosaur on his way home to Clawtooth Mountain.

Maybe you don’t think you are brave because you feel afraid. But courage isn’t about what you feel son; it’s about doing the hard thing despite what you feel. It’s about coming to Wednesday Night even though there are lots of kids making lots of noise. It’s about getting in the car and going to school even though everything inside you craves the safety and peace of your living room. It’s about walking into a hospital waiting room even though you know the pokes are coming.

This is what you showed us so clearly last month, son. It’s what you show us every day.

Next year, you’ll be a teenager. We’re about to walk into a brand new wilderness. Both of us. But if you can face your fears, then I think I can face my own. We can face them together.

Happy birthday, little Arlo. And I’m proud of you.

Dad

]]>

He refuses to step foot in there now, so he sits with the adults through both the singing and the sermon, eyes glued to a visual timer on his mother’s iPhone.

It’s not a bad trade, in one way. Sara and I would prefer our son to join the congregation and be with his peers, but the arrangement has complicated all of our lives. We work at church, but the whole place makes him antsy now. Someone always has to sit with him through the service in case he tries to bolt without warning, or randomly yells “Syndrome’s remote!” from the Incredibles. Both have happened.

When Jack was little, this kind of thing wasn’t a big deal. We would take the same approach as we would with any of our other kids: we would simply pick him up and carry him into the room against his will. Because he would be fine. Kids get over things quickly, right?

Well, maybe, but he is eleven now, and he’s getting stronger from all that sock flapping. He’s almost as tall as his sisters, and his will has only hardened in his growth spurt. It’s no use trying to force him to do anything he doesn’t want to do. More to the point: it is counter-productive.

The “pick him up and make him go in” phase of parenting is supposed to be short.

Small children are too young to understand why they must brush their teeth every night, or why they have to fasten their seat belts, or why they have to go to class. As parents who do understand, we sometimes have to make those decisions for them. They are growing, however, and soon, they will have to choose on their own. We won’t be able to carry them in anymore.

How do we prepare for that eventuality? By ceding control in small increments. We phase out coercive parenting little by little, and begin to lead instead through influence. We begin to regularly offer them choices, and we explain why some choices are inherently better than others. And while we do all of this, we hope and pray that our children’s comprehension will grow apace with their stature.

But there’s the rub. This hasn’t happened with Jack. In many cases, his understanding (as far as we can tell) hasn’t kept up with his limbs. Sometimes he is just being stubborn like any other eleven year old, sometimes he is overstimulated and overwhelmed, but many times, it seems like he truly doesn’t get it.

My boy is growing, and it’s exciting and wonderful and scary and endlessly complicated.

So how do we lead him? Certainly not by authoritarian measures. Coercion is a last resort now. Jack’s will has begun to blossom, and our tactics have necessarily changed. We have had to stop pushing and start leading.

I suppose in this way, my son is not any different than the rest of us. In order to lead him, you have to invest in him. You have to walk beside him. You have to show him you care about him. You have to build trust, and trust-building takes time.

In our current struggle, I am grateful to have friends who live this principle. Isaac and Lori, who often work with Jack on Sunday mornings and Wednesday nights, are playing the long game, opting to guide him gently. They’ve sat with him. They’ve talked with him. They’ve taken walks past the big, scary door to the Open Heavens Room, and have assured him that everything is going to be okay.

This is what real leadership looks like, and it’s beginning to pay off.

Jack is starting to come around now. He even took a couple steps through the door last week. He kept his eyes shut, but he did it. You can see it in Isaac’s video below.

It will take more time, though, and that’s okay. This is our life now. We don’t rush things anymore. The days of causation and coercion are coming to a close. This is the age of coaxing and calling; of hand-holding and shoulder squeezing; of “take a deep breath, son” and, “you can do this, buddy. I know you can.”

And he will. Just wait and see.

(Many thanks to Isaac for the video and for the patience. We are fortunate to have you in our lives.)

Feature photo by Anne Nunn Photographers

I heard your footsteps at midnight last night, fast and frantic. They took you to the sofa in the dark. I found you there and asked if you were okay.

“Did you have a bad dream?”

You didn’t answer.

“It’s okay. It wasn’t real, buddy. “

I tried to lead you back to your room with your bedding and favorite pictures—items that whisper of safety and home. Your yanked your hand back in protest and yelled,

“No fank you! No fank you!”

So I brought your pillow to the living room and wrapped your stiff frame in your blanket. You had to turn it the other way round so the soft side was up. I muttered my apologies. I know that’s how you like it. It was just dark, and I was half-awake.

Then, you just sat there, still and stoic, leaning into the arm of the sofa. I couldn’t see your eyes, but you did not object when I went back to bed.

Your mother was breathing softly next to me. I lay there wondering about your anxiety, and why you feel the world has turned against you this year. It’s not just bad dreams. It’s everything. The Oregon countryside used to give you delight. The lakes and riverside trails would brighten your eyes. Swimming and exploring brought your laughter and joy. You were an outside boy.

This year, though, the open air has morphed into your enemy. We can’t figure out why. You have become the keeper of the sliding glass door; it must stay shut. Always. You never spin in your outdoor swing anymore, and you don’t want to join us in the back yard even for evening campfires. The only way we can bring you to the lake or to the park is if we bring your traveling tabernacle: a little blue tent and a timer. You will sit in there and stare at the countdown clock as it ticks back down to home.

Then there’s your OT appointments. Miss Molly was one of your very favorite people in the world. But now you don’t even want to go. You love these people, son. You love these places. I promise, you do.

In the darkness, you interrupted my thoughts with a frantic cry, “Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!”

I rushed back out to the living room. Then, you gave one of those perfectly-timed, fully-formed movie quotes that continue to astonish us:

“I am completely terrified.”

It’s a line from Happy Feet, apparently, where a penguin is alone on a floating chunk of ice in the ocean. Your voice was flat with those borrowed words, but I could feel the emotion in the tight grip of your fingers. You wouldn’t let me leave.

And then I remember that other line you’ve been quoting so often from The Good Dinosaur: “I ain’t a coward!”

No. You’re not a coward. What causes your nerves to awaken like this, son? What is it that stiffens your limbs and sends your heart pounding?

Maybe that’s a silly question, though. The fact is, for the past two months, I’ve been stiff and skittish, just like you. It’s this book I’m writing, I think. It’s hard for me to dig up our story—yours and mine—without also digging up the bitter water I drank for so long. That water made me unsure of myself. Of everything, really. It made me run away from things that did me good.

We all do that sometimes when we are scared and hurting. We lose track of the things that refresh us and bring us joy. We think, “I’ve changed. I don’t like these things anymore.” but we haven’t really changed. Our hearts have just forgotten, that’s all, and they need to be reminded.

You and I have both come so far the last few years, and this is what troubles me. It feels like we’ve regressed again. It feels like the anxiety is pulling us both backward, and it’s hard to find our deep gladness. I can see what is troubling me, but what about you? What makes you afraid? What makes you forget?

Sometimes, when you panic at bedtime, you scream for the “Jesus Storybook Bible.” Your favorite is the “Captain of the Storm” story, where people in the boat are so scared until Jesus speaks to the wind and the waves. Then, the peace returns.

You love that story, I think, because it is your heart’s prayer: you want our impossibly loud and blinking world to calm down. You want to breath easy again and rediscover stillness. Know this, my son: it is my prayer, too. I’m in that boat with you. So let’s hold to one another tightly. Let’s look up together and listen again for the whispers of Home.

Image credit: my daughter, Jenna

]]>“Jack, this is gross. You’ve got to stop touching the screen, especially after you eat those cookie balls.”

He wouldn’t acknowledge me, except to parrot back a few words as if to mollify my frustration.

Our television is raised up fairly high, and Jack, my eleven year old autistic son, has been secretly smuggling chairs into the living room in order to get high enough to touch the top of it. Part of that, I suspect, is an attempt to mimic Arlo from Pixar’s The Good Dinosaur, who reaches up high with his foot and says, “I’m gonna make my mark.”

But there’s more to the mystery than that. The fact is, our boy has been bringing a little extra OCD to the autism party as of late. He refuses to enter the special needs room at church. He gets frantic, kicking and screaming with a “there’s-a-great-white-shark-in-the-room” kind of terror. And at home, he melts down at our gentlest prodding to go on a bike ride, or to do anything, really, that he doesn’t want to do. The screaming that follows the words “back yard” must raise eyebrows in the neighborhood from time to time. He won’t touch my phone (he’s scared of that, too), and now he won’t even touch some of his treasured laminated pictures that literally line our bookshelves. Yet he will touch the TV screen. Often. Just another puzzle…

Seasons like these can be draining, because the boy won’t give an inch. He would fight every battle if we let him. We have to pick where to aim our energies. It can be a bit depressing. The world requires flexibility of its citizens, and he is more inflexible today than he’s ever been. What will all this mean for his future?

Seasons like these can be draining, because the boy won’t give an inch. He would fight every battle if we let him. We have to pick where to aim our energies. It can be a bit depressing. The world requires flexibility of its citizens, and he is more inflexible today than he’s ever been. What will all this mean for his future?

But then, these seasons contain reassuring moments, too. Case in point: on Friday, I came home with my daughters in the late afternoon, and Jack and Sara were alone in the house. The soundtrack from The Good Dinosaur was filling the house, and Jack was curled up beneath his favorite blanket with his new penguin book. He was in his happiest place, and his face showed it. When he saw me, he beamed as if to say, “Dad you’re home! Now I have everything I will ever need.” And it made me think of the first penguin book and the moment three years ago when everything changed. He wore the same smile.

I saw something else the next day, too. Through open door in my bedroom, I could see Jack sneaking the chair beneath the tv, and climbing on it. There was no movie playing, only various pictures floating slowly upward. Our AppleTV screensaver was set to National Geographic wildlife images. Jack reached up with one finger. The screen distorted to purple around the spot he touched. Irritation flashed in me. He’s going to ruin that screen, I thought, sitting up.

Then I saw it. A penguin. He was touching all the penguin pictures.

I sat back down and closed my mouth. In a season of such sticky obsessions and meltdowns, the boy still draws strength and peace from his penguins. It started with the original Jack and Daddy book. He remembers it as well as I do. It’s why he has been keeping this new book close to him, and why he’s asking to watch the penguin documentaries on Netflix. We are a story family, and penguins were Jack’s very first metaphor. They stand for me and him. For us, together. More broadly, penguins represent family.

I’m writing about this today to remind myself how much it all matters. I am speaking to my own soul. True, right now, the horizon doesn’t look especially bright. Jack is eleven. Soon he will be a teenager. His intensifying behaviors are going to complicate his transition into adolescence. All our concerns about his future feel more solid than ever.

And yet, our greatest concern has been assuaged once and for all: Jack is not oblivious to his family’s affection. Rather, he is still captivated by it. He loves us and we love him. He may not be able to tell us in sentences, but he can show us with a picture.

So there goes my son now, pushing his chair further into the living room and deeper into life. We don’t know what storms this season might bring, but our boy is not alone. He is armed with the power of a metaphor, and with it, he will find a way to stand tall. He will make his mark.

Feature image courtesy of the always awesome Anne Nunn Photographers.

]]>But even the spell of the New York couldn’t shake me from the fact that I was right and my friend was wrong, and I had to keep telling her. We had just seen Miss Saigon on stage, the famous story of a Vietnamese orphan girl and her American G.I. lover. Their romance produced a child, but the soldier had already gone home, leaving her to provide for her son as a dancer and prostitute (I might have some of the details wrong here. It’s been twenty years…).

“She was desperate,” my friend said. “What do you expect a mother to do?”

“It doesn’t matter. That lifestyle is wrong,” I told her.

She was done discussing it, but I wasn’t, so I kept pushing. Kept hounding her.

I don’t remember what I said, but I remember it was too much. My friend knew this side of me well. I was a brash eighteen year old who had to have the last word. She usually rolled her eyes and let me have it. That night, though, I’m pretty sure I made her cry.

When I think of that year, I think of the hit song that dominated our mix tapes: “The Freshman” by The Verve Pipe. The sad, grungy ballad opened with the words, “When I was young, I knew everything.” How fitting that I never understood the line back then.

I wince when I think of those days. I wince because of the essay I wrote and read aloud in English class: how to always be right about everything. I wince because of the stupid thing I said in my speech on graduation night: “I can’t wait to throw my two cents into the arena of ideas.” I didn’t have two cents of my own to throw. I had pennies borrowed from other sources–some of them wise, but most just loud. I wince because even though I had never experienced a lick of genuine hardship, I walked with an arrogant strut, blasting my beliefs without a shred of gentleness or humility.

And of course, nothing has gone according to plan since then. It never does. Rather than changing the world with my big ideas, the world broke me.

***

“For the life of me, I cannot remember what made us think that we were wise…”

It is a cliche to say that men are fixers, and that cliche doesn’t fit me anyway. I don’t fix things; I have friends who fix things I break. But even for the inept guys like me, the stereotype usually fits. We crave resolution. We lean into it. When we don’t get it, we fall off our axis. Our worlds start to tilt.

My world tilted eleven years after I graduated from high school. Within fifteen months, I lost a dear friend to cancer, my infant son underwent open-heart surgery, and my three year old drifted into the fog of severe autism. For me, this triple-blow was especially debilitating, because up until then, I had never experienced one real crisis let alone three.

Answers had always come easily before that storm. Theology and logic had been obvious things. Truth glimmered so brightly, I wondered why everyone couldn’t just see it. Not after that.

Jack’s autism was the hardest because it lingered. It still lingers. And even though I’m not walking in perpetual numbness and sorrow anymore, his wordlessness, his seizing, his panic attacks and overwhelming shrieking… those things still throb beneath my surface. I can’t bring resolution to those pains in him or in me.

And yet those same pains do some good. They make me more aware of my need for God and for renewed redemption. They remind me daily that I am inept at life, and that I don’t have all the answers. Not anymore.

***

“And now I’m guilt stricken…”

It’s been twenty years since I hounded my friend about the themes of goodness and morality; twenty years since I donned the cap and gown and charged into a world I couldn’t possibly understand. I don’t know half as much as I did then, and yet here I am, dealing out words and assertions for a living. It’s a little terrifying. I’m a teacher and preacher, and my writing is starting to reach larger audiences. I’m thirty-eight years old, which is safer than eighteen, I suppose, but I still look back at pieces I wrote just a few years ago and I wince again. Was I too flippant? Were my words haughty? Or maybe I went too far the other way, pulling punches beneath the ghost of an eighteen year old ignoramus. Will I ever be wise and gentle enough to say anything without regret?

It’s been twenty years since I knew everything, and I want to take it all back. I want to tell my old schoolmates I’m sorry for my arrogance; for my snotty, brutish arguments that carried neither substance nor kindness; for my hasty opinions and unfeeling judgments, and for the way I looked down on those who were limping. Forgive me. I hadn’t been broken yet. I wish I had been broken earlier. I can only pray I am broken enough now.

]]>

Anxiety attacks have haunted Jack nearly every day this month. They’re not temper tantrums. Rather, they’re like onslaughts of sheer, icy panic; floods of emotion he can’t hold back. He runs toward the nearest glowing screen and starts pushing buttons—a digital itch he must scratch. We tell him, “no movies, son,” and he begins punching his forehead. We raise our voices, but before we even get the words out, he screams, “No helmet!”

“Stop hitting yourself, then,” we say.

Then, the tears spill out in shrieks. All we can do is pull him close and whisper his requested reassurance: “first sleep, then morning, then Cars 2.”

It happened Monday night when I was alone with the boys. His 5 year old brother set him off with an actual temper tantrum. Jack couldn’t recover, and he ended up huddled close to me on the couch. “I love you, son,” I told him. Our heads were touching. “First sleep, then morning, then Cars 2.”

On evenings like that, I often feel the old tug of despair on my sleeve, and the temptation to let it wash over me like it used to: Jack’s anguish; his future; our lack of connection. It still gets the best of me from time to time. But on this occasion, the sadness didn’t win. It couldn’t win. Not after what happened the day before.

***

It rained during the 5K Race for Autism, but nobody cared. They are Oregonians, after all. Some didn’t even bother with sweaters or raincoats, letting Team FlapJack shirts shine with pride. The blue was more prominent than any other color or costume theme. A team of over sixty. You couldn’t miss us.

I stood next to the boy himself, who was wearing a brown coat over his own blue. We had talked about the race all week long.

“Look at all these blue shirts, buddy. They’re here for you!”

Half my church showed up, and others too. Old friends. Former teacher. Staff from his early intervention years. Even his beloved Mrs. E. When he saw her, he leaned in with an expression of dazed wonderment that spoke more clearly than words ever could: “I can’t believe she’s here.”

Indeed, I couldn’t believe they were there, either. All of them showing their support for my family. All of them cheering on my boy. So many of them. And the other teams, too, all celebrating beloved children who are so often forgotten. So much joy.

The race was cold and beautiful. We wound through a riverside park, past Autzen stadium over a long footbridge, and back along the edge of the University of Oregon campus. A caravan of friends ran with me to keep me honest. I didn’t want to walk this thing. I wanted to run it through to the end. They didn’t have to prod me much, though. With a pack of friends running the same race, who needs policing?

***

I sat in Doug’s office the next morning and reflected on it all. Doug is a mentor and a friend who has walked with me through the thick depressing years, and prayed me through my innumerable ups and downs.

“Let yesterday carry you,” he told me.

I knew at once what he meant. All those beaming faces, the sea of royal blue runners, the overwhelming show of support. Not every day is like that, but Sunday was. Sunday was solid and real. Sunday could never be taken away from me. It ought to be a stake in the ground; my stone of remembrance.

And this advice was coming from a man who’s just been walking through the greatest, most painful trial of his own life. His wife of over forty years is battling severe Alzheimers. His best friend is slipping away by inches. He knows all about ups and downs, bright days and dark ones. Memories are more than gold-laden treasures; they are his swords.

In a culture so enamored with romantic tragedy, it sounds almost naive to think that memories can be used to fight despair rather than lead to it.

Here in the west though, despair is as decorative as a henna tattoo. In our worst moments, we are the goths, dressed in midnight and hellbent on mourning. Our laughter is bitter and hoarse, our diversions dark with apocalyptic foretelling, and even the pineapple rays of sunshine just serve to make the shadows more stark. Joy becomes a scarlet letter worn by the privileged few who are not outraged, and therefore not paying attention.

“How can we celebrate while the innocents suffer?” they demand. We stutter, so they press on, insisting the party-goers silence the whooping and whistling, and all the waving of palm-branches; that deliverance is a myth as long as some innocent still sits in a cell, and we all know injustice abounds.

So round and round we go on a carousel of hand-wringing and hashtags. Happy faces are all ablur and out of touch. We have no time for them. Days gone by are faded cold. We have no time for them. And hope for tomorrow hides beneath our beds like a monster waiting to see the skin of our ankles.

In such a culture, it feels natural to surrender to it all, because despair is easier than joy. Despair is memory foam, yielding to the weight of the worlds we carry on our shoulders.

Joy, though… Joy makes demands on us. Joy insists I remember that I am small, and my drama is limited. Joy asks me to offer thanks to God for his gifts even while they elude me. I might be barren, but a couple down the hall just delivered. I might be living in a drought, but somewhere, some thankful farmer is dancing in the rain. My current experience is simply not wide enough to define eternal truths. Creation cannot be wholly bitter at least, in a world of newborn children. As long as there is laughter, reality can’t be wholly cruel, and God can’t be wholly unseeing.

Even on days when the wine dries up, the dancing music goes silent, and there is no merriment to be found, we can, at least, hold in our minds the paintings of better hours. Those pictures are whispered reassurances from a calming Father, “there is still beauty. It’s not all used up.” And on the blue-shirted backs of these memories we climb, and ride them through till morning.

Images provided by my friends Jaymie Starr Photography, Ariah Richardson, and Chris Pietsch of the Bridgeway House. Thank you all!

]]>We talk a lot about the need to be loved, but by that, we usually mean the big, obvious kinds. We need agape love, unconditional affection from our parents, our families, and from God. We feel the need for eros, romantic love with sexual expression. But we talk less of our need phileo, the deep, friendship variety. Brotherly love, as it’s called.

As D.C. McAllister wrote, phileo is “a kind of love we desperately need in our lives—passionate, nonsexual love. But we’re so uncomfortable with the expression of intimate, familiar feelings among men that we’ve given it its own name—bromance.” She’s right. Phileo has become a pop-culture punchline. I have to think that is part of what’s driving the trend toward isolation. We don’t take friendship seriously.

Phileo is a need. So why do I run away from it?

When describing my autistic son’s initial regression, I often say he went into a fog. He became distant, he lost his vocabulary, and he refused to look us in the eye. What I don’t say often is that I followed him. I went into my own fog. I became sluggish, troubled, and increasingly introverted. While Jack drifted into autism, I drifted into depression. And I fed that depression with a self-imposed isolation.

Sorrow hung over me for years. I had friends, but I didn’t call them. Instead, I would fold myself into my laptop, plug in some earbuds, and tune out the helplessness, even while my kids tried everything short of setting my socks on fire to get my attention. I would offer a wry nod, then go back to whatever on-screen emergency I had just invented.

Studies show that parents of special needs kids have significantly elevated risks of anxiety and depression.

That makes sense. The physical strain of sleepless nights, the psychological fears of wandering, bullying, and the future all contribute to that risk. But for fathers at least, there’s another factor. Men are fixers. I know, that’s a cliché, but there’s a reason for the stereotype. Men crave resolution. We lean into it. And when we encounter something we can’t resolve — especially something as confounding as autism — we lose our sense of equilibrium. Our confidence comes crashing down.

I wasn’t seeing a counselor during my dark season, but I was fortunate enough to have my boss and senior pastor, Joshua, down the hall. For months on end (or was it years?), I would sit in his office and fall apart on a weekly basis. In retrospect, it wouldn’t have hurt to double down with a therapist.

But then, what are counselors if not friends we pay for out of desperation?

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a wonderful and immensely helpful profession, but if people talked to their friends more often—-I mean real conversations in the bond of phileo-—don’t you think many of us would find healing organically?

I had organic friends. I just didn’t hang out with them. And for that reason, it took me far too long to mend.

Then one Sunday, I was onstage preaching about going through pain, and it all came out in a rush. Jack was going through a frightful season, and we were all hurting with him. I ended up awash in tears. Big, ugly tears.

When it was all over, two men stood at the foot of the stage, looking up at me with red eyes of solidarity. Two good men. Friends. I stepped toward them, and they embraced me together without shame. I wept some more, right out in the open. I think they did, too.

And at that moment, I swear I heard a whisper deep inside me: “I have given you brothers.”

Indeed, I have brothers, but even years later, I still have to fight the urge to live as if I don’t. Because I’m a man, see, and “I got this! What? You don’t think I got this?”

Yeah… I don’t got this. “It is not good for man to live alone.” We quote those words at weddings, but it’s as true for phileo as it is for eros. It is not good for man (or woman) to live without friends. We are relational beings, like it or not. When we pull away from relationships, we suffer. That is part of our design. Life is built to be shared, not hidden.

I recently joined some guys for a weekend at the coast. I was too busy to go, but I went anyway. We had no agenda, and ended up wasting time together over beach bocci ball, grilled meats, and an assortment of grizzly banter. But of course it was more than that. We were sharing troubles. We were trading life. We were lending strength.

One of those mornings, I walked to an overlook at Seal Rock beach, the same hidden paradise where we shot our viral video last summer. For an instant, it was as if I stood above my entire journey with Jack. All the heartache of his diagnosis, the depression, the growth and the setbacks, the hiddenness turned shockingly public with a single upload—-all of it hit me afresh. And again, I heard the words, “I have given you brothers.”

I am glad to be out of the fog, and to see the path again. But most of all, I am grateful I do not journey alone.

***

Feature image provided by Daniel Horacio Agostini at Flickr.com under Creative Commons License.

]]>