You Are Enough (A Letter to My Autistic Son on his 15th Birthday)

Dear Jack,

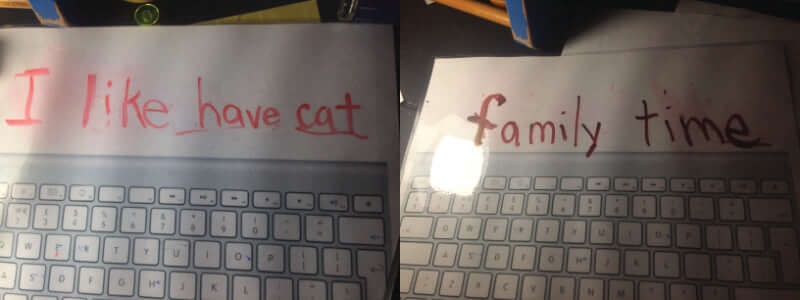

Over the past several months, you and mom have been working at the kitchen table with your communication device. Since spoken words are still so tricky for you, we’re exploring this other way of talking. You touch the screen and choose between picture icons, common words, and a qwerty keyboard. When you find what you want, you string the words together, and the iPad says them aloud: “I want pizza.”

We’re not sure whether this will, in time, become your preferred way of talking. After all, you can tell us with your lips that you want pizza. You do that kind of thing all the time. But something different has started to happen with this new way. You’ve started making observations.

“Can you tell me something about this picture?” Mom will ask, sometimes with the help of the teachers on Zoom. It’s usually a picture of something you know: Mike Wazowski, or Kermit the Frog, or maybe even a real frog. This time, it was Moana.

I think the request didn’t make sense to you at first. Why would we want to know what you see in the picture? Can’t we see it ourselves? But they kept asking you, and you started to play along.

“Moana is pretty,” you said with the device.

Well then. Yes. Yes, she is. I’m not at all surprised you noticed that. You’re turning fifteen, after all. I was younger than you are now when Beauty and the Beast came out, and I noticed the same thing about Belle. Part of me is still a little bit in love with her, I think. So no, I wasn’t surprised at all. But we were all still excited to know it simply because you thought it.

And what about Maui? What did you notice in the picture of the gargantuan demi-god? The teacher asked the question, and you thought about it. You searched for available answers under the “S” listing. Mom thinks you were looking for “strong.” But it wasn’t there. So you backed out and found another word, which featured a stick man lifting weights with one hand. You clicked on it.

“Easy,” the device said.

Easy. Of course. He’s so strong, he can pick up boats and trees and probably mountains without breaking a sweat. Everything Maui does is easy.

“Jack, that’s so smart,” mom said. And she meant it. You gave a great insight. You saw a picture everyone else saw, and you shared your own, personal, Jack-thought. And it was a cool observation.

Maybe this doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, son, but it is to us. Your thoughts matter to us. Your thoughts are important. Your thoughts tell us more about you, and we want to know you as much as we possibly can. This is why we spend time working on the device even though it’s hard. It’s also why I often say things like, “what are you thinking about, bud?”

I’m explaining this because I am afraid we might sometimes give you the wrong idea. We might be accidentally hurting your feelings. Moms and dads do this kind of thing without ever knowing it, and then when their kids grow up and tell them, everyone feels bad. And one of the biggest ways this happens is when kids feel like they have to perform for their parents’ affection.

Some boys, for example, feel like they have to play football or basketball really well so their dads will be proud of them. Some girls feel like they have to get good grades and be perfect so their moms will think they’re valuable. And others—kids who have autism and have a hard time communicating—might feel like they have to talk to prove their worth. I hope and pray you don’t feel this way, but I know the pressure might be there sometimes.

Remember when we stayed at the cabin last summer? You loved it. We could see it all over your face. Maybe it was the way the lake was nestled into mountains, or how the sun hit the dock in the afternoon. I was sitting with you on the dock one of those afternoons, and you wore a serene smile. I asked you, “What do you like most about this place, Jack?”

You looked at me, and your mouth was open just a little bit. It seemed like you were considering the question and wanted to answer. And for just a moment, I thought you might do it. I thought you might say, “I like the color of the water,” or, “I like having Leeli here.”

Could you tell how much I was hoping for that to happen? And did it make you sad when you couldn’t do it? Did I accidentally put pressure on you to perform?

My dear boy, we have shared fifteen years of life, and of all the things I have spoken to you, this might be the most important: you are enough.

That’s it. You’re enough.

I love it when you can tell us what you think. I love it when you can communicate what you want. But you do not have to do those things to earn our affection. You never did. And if I’ve ever—even for a moment—made you think otherwise, I pray you can forgive me. Because there is a difference between what a boy can do and who a boy is.

Remember the “Jack and Daddy video” on the beach? I told you then that you were “a piece of God’s own daydreams.” I meant it. That is who you are. You are the flesh-and-bone dream of the Creator Himself. You carry His image, and our image, too. You are priceless to us, not because of anything you can accomplish, but because you are our son. You don’t have to talk about the lake or about Moana to prove it. You don’t have to do anything to prove it.

Work time isn’t going away, I’m afraid. It’s part of growing up. Sometimes I don’t like it very much, either. But we are so proud of the way you face the challenges. We know you’re not Maui. We don’t expect you to be like him. None of this stuff is easy. It’s hard, and yet you keep at it.

We’ve told you we want to hear your thoughts, son. Well, it seems like you’re starting to believe us. And now, I am asking you to believe this: we adore you, even when the words don’t come.

Happy Birthday,

Dad

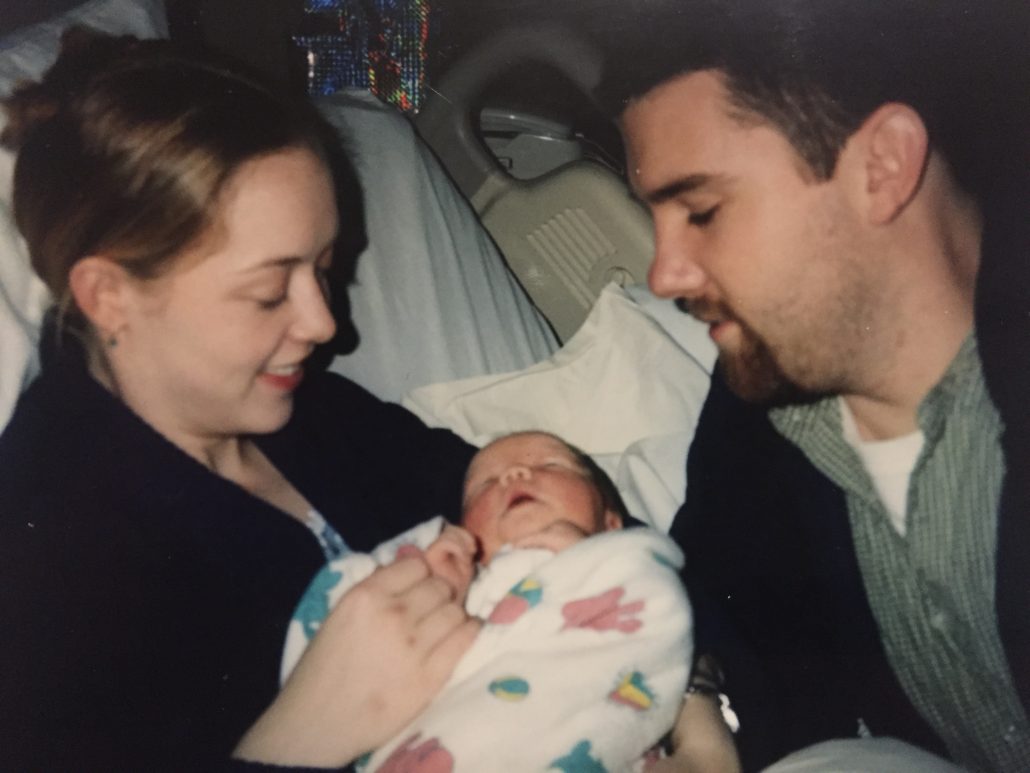

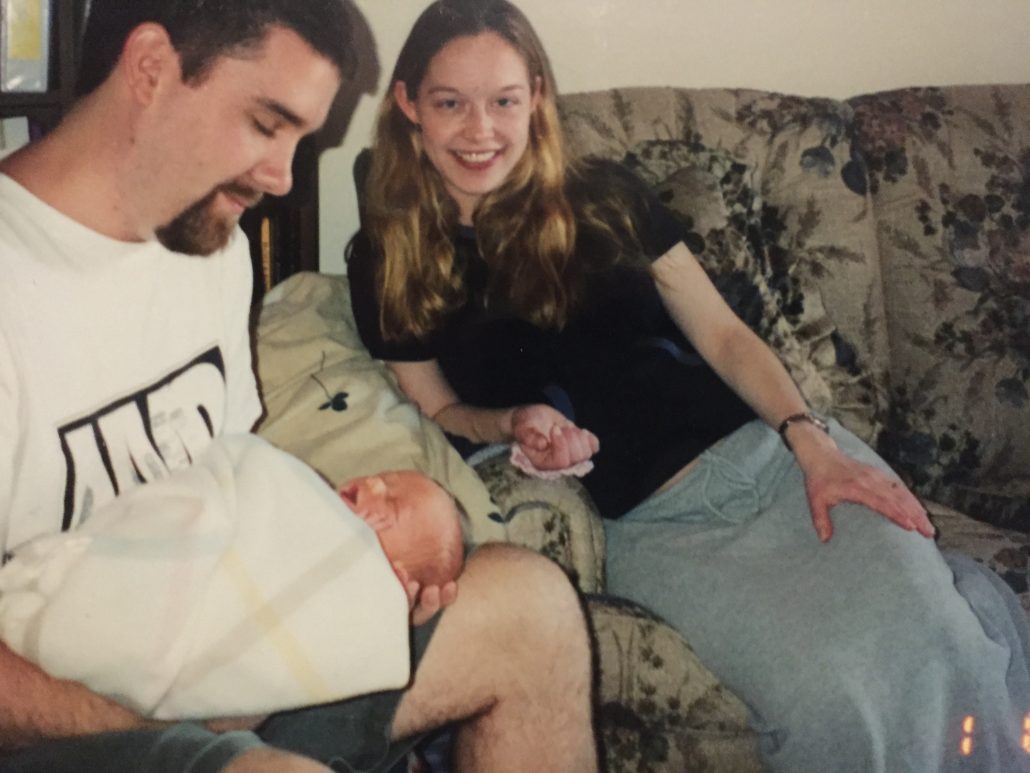

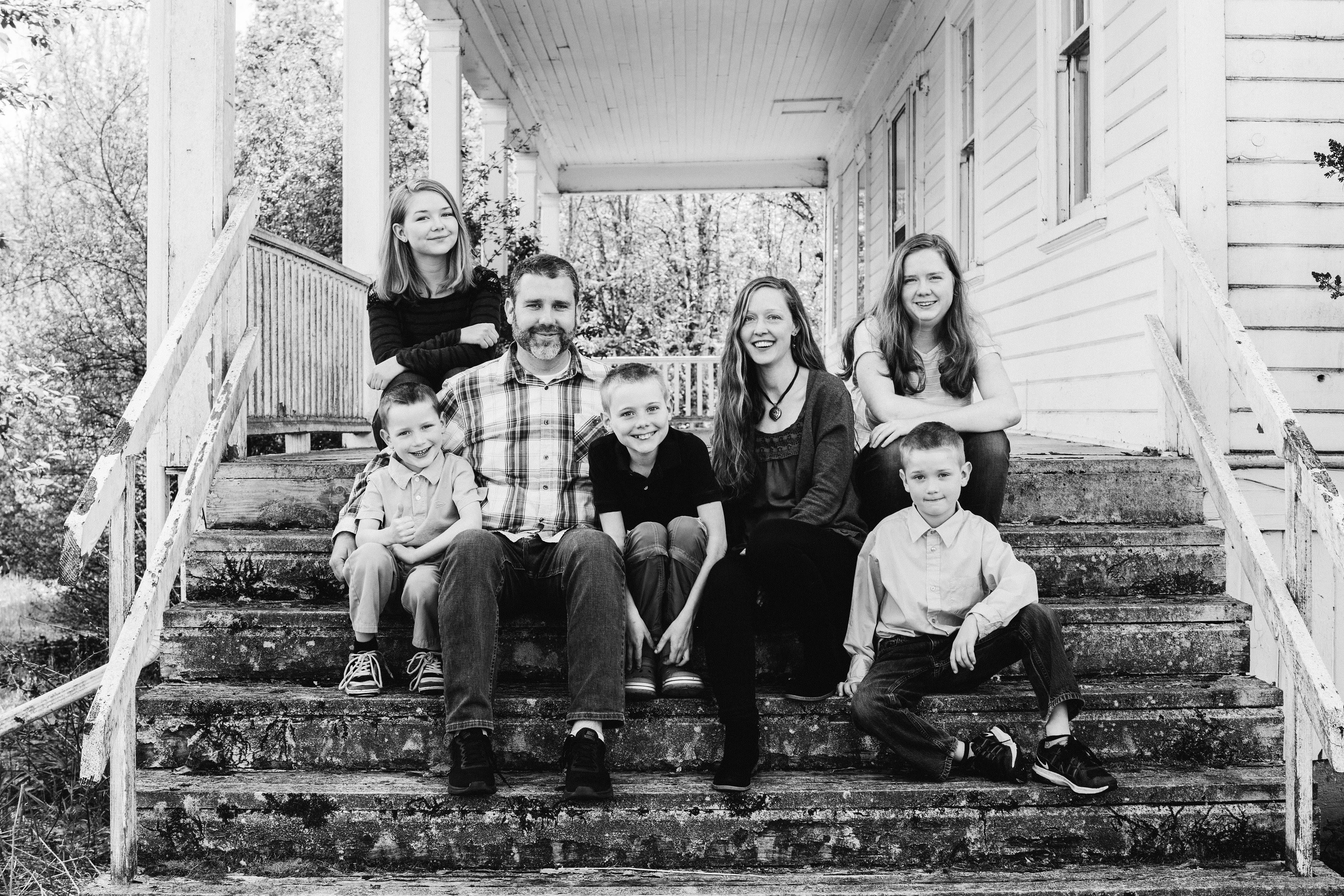

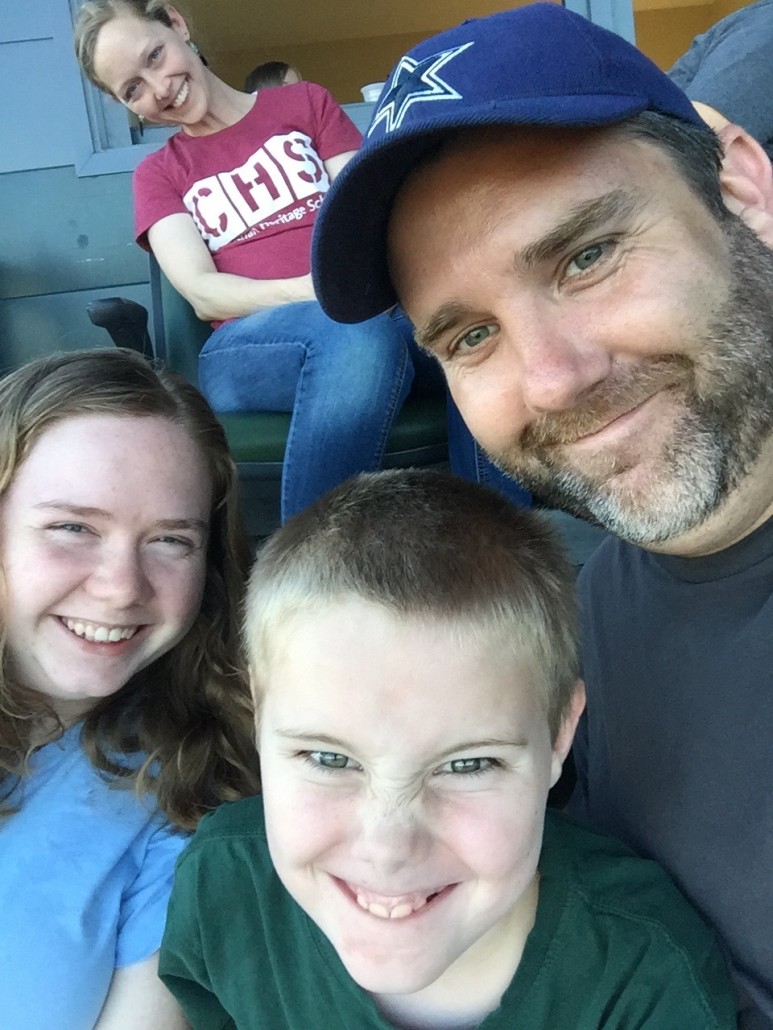

Many things in your world are changing. Your big sister just turned eighteen, for one thing. Soon, she will go to college, and she will leave her bedroom. We won’t see her as often because she will be making a new life with studies and friends, and I imagine she’ll even have her own family someday. You will miss her. We all will. But it will be a good kind of pain.

Many things in your world are changing. Your big sister just turned eighteen, for one thing. Soon, she will go to college, and she will leave her bedroom. We won’t see her as often because she will be making a new life with studies and friends, and I imagine she’ll even have her own family someday. You will miss her. We all will. But it will be a good kind of pain.

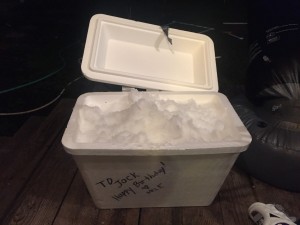

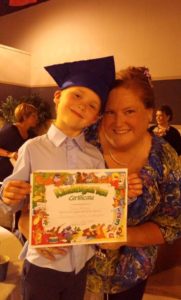

Janae was in our lives for sixteen years. Sixteen. And in those years, she brought to my family a brand of lavish affection we didn’t know existed. She was both the children’s godmother and their fairy godmother, granting movie nights and birthday wishes with a winsome wave of her wand. And to Sara and I, she gave a loyalty and presence we never expected and did nothing to deserve.

Janae was in our lives for sixteen years. Sixteen. And in those years, she brought to my family a brand of lavish affection we didn’t know existed. She was both the children’s godmother and their fairy godmother, granting movie nights and birthday wishes with a winsome wave of her wand. And to Sara and I, she gave a loyalty and presence we never expected and did nothing to deserve.

That was my sister. We had different parents, but for the past 16 years, Janae Alice McWilliams was a staple in the Hague household. She was a part of us. When we left Texas for California, we left together. When we migrated from California to Oregon, we migrated together. When we lost our dear Karen, we mourned together in the little house we shared for more than three years. She was my kids’ auntie and chief cheerleader; their personal, in-home Mary Poppins. She went to dance recitals and soccer games, and when Sara and I couldn’t make one of those events, we never worried too much. Janae could be there. That would be plenty for the kids.

That was my sister. We had different parents, but for the past 16 years, Janae Alice McWilliams was a staple in the Hague household. She was a part of us. When we left Texas for California, we left together. When we migrated from California to Oregon, we migrated together. When we lost our dear Karen, we mourned together in the little house we shared for more than three years. She was my kids’ auntie and chief cheerleader; their personal, in-home Mary Poppins. She went to dance recitals and soccer games, and when Sara and I couldn’t make one of those events, we never worried too much. Janae could be there. That would be plenty for the kids. own absent-minded minimalism. Truly, she was my sister, but we could never have grown up in the same household. Her grand gestures always dwarfed my own feeble attempts at appreciation. She gave the best, most thoughtful birthday presents. I gave her gift cards. That kind of thing always embarrassed me, but how could I compete with her? How could anyone compete with her?

own absent-minded minimalism. Truly, she was my sister, but we could never have grown up in the same household. Her grand gestures always dwarfed my own feeble attempts at appreciation. She gave the best, most thoughtful birthday presents. I gave her gift cards. That kind of thing always embarrassed me, but how could I compete with her? How could anyone compete with her? wild words of praise; with long conversations, deep embraces, and clocks on the wall. She spoke all five love languages with a native accent.

wild words of praise; with long conversations, deep embraces, and clocks on the wall. She spoke all five love languages with a native accent. But sometimes, he can be such a jackass!” We all fell apart laughing. It was perfect. But it also stung just a tad. Not because she was wrong; I know full well that I can be a jackass, and I didn’t mind her saying so. No, it stung because of where my mind flashed to; the times I hurt her like almost nobody else could. Like when I took her for granted, as if her die-hard devotion to me and my family was somehow pedestrian; as if it was a small thing to hear people gape at how much she loved us; as if her unassailable, self-sacrificial loyalty to the Hague clan was our right, and not her gift.

But sometimes, he can be such a jackass!” We all fell apart laughing. It was perfect. But it also stung just a tad. Not because she was wrong; I know full well that I can be a jackass, and I didn’t mind her saying so. No, it stung because of where my mind flashed to; the times I hurt her like almost nobody else could. Like when I took her for granted, as if her die-hard devotion to me and my family was somehow pedestrian; as if it was a small thing to hear people gape at how much she loved us; as if her unassailable, self-sacrificial loyalty to the Hague clan was our right, and not her gift.

know they say not to have regrets, but I have them. I think it’s okay to look back and wince every now and again; to hope that our love was wide enough, and to trust that even where it wore thin, things might still be okay. Because whether we pack heavy or pack light, this life is a temporary destination. Eventually, we will go home, and Someone else will have to carry us up the stairs. We will have to trust that His love is full enough to make up for all the places ours wore thin.

know they say not to have regrets, but I have them. I think it’s okay to look back and wince every now and again; to hope that our love was wide enough, and to trust that even where it wore thin, things might still be okay. Because whether we pack heavy or pack light, this life is a temporary destination. Eventually, we will go home, and Someone else will have to carry us up the stairs. We will have to trust that His love is full enough to make up for all the places ours wore thin.

Today, Kyle is sixteen years old, and he is a paid member of our church staff. He worked himself into a job. He has grown into a kind, hard-working young man, and is a true asset to our team. The guy just gets stuff done, and we love having him around.

Today, Kyle is sixteen years old, and he is a paid member of our church staff. He worked himself into a job. He has grown into a kind, hard-working young man, and is a true asset to our team. The guy just gets stuff done, and we love having him around.

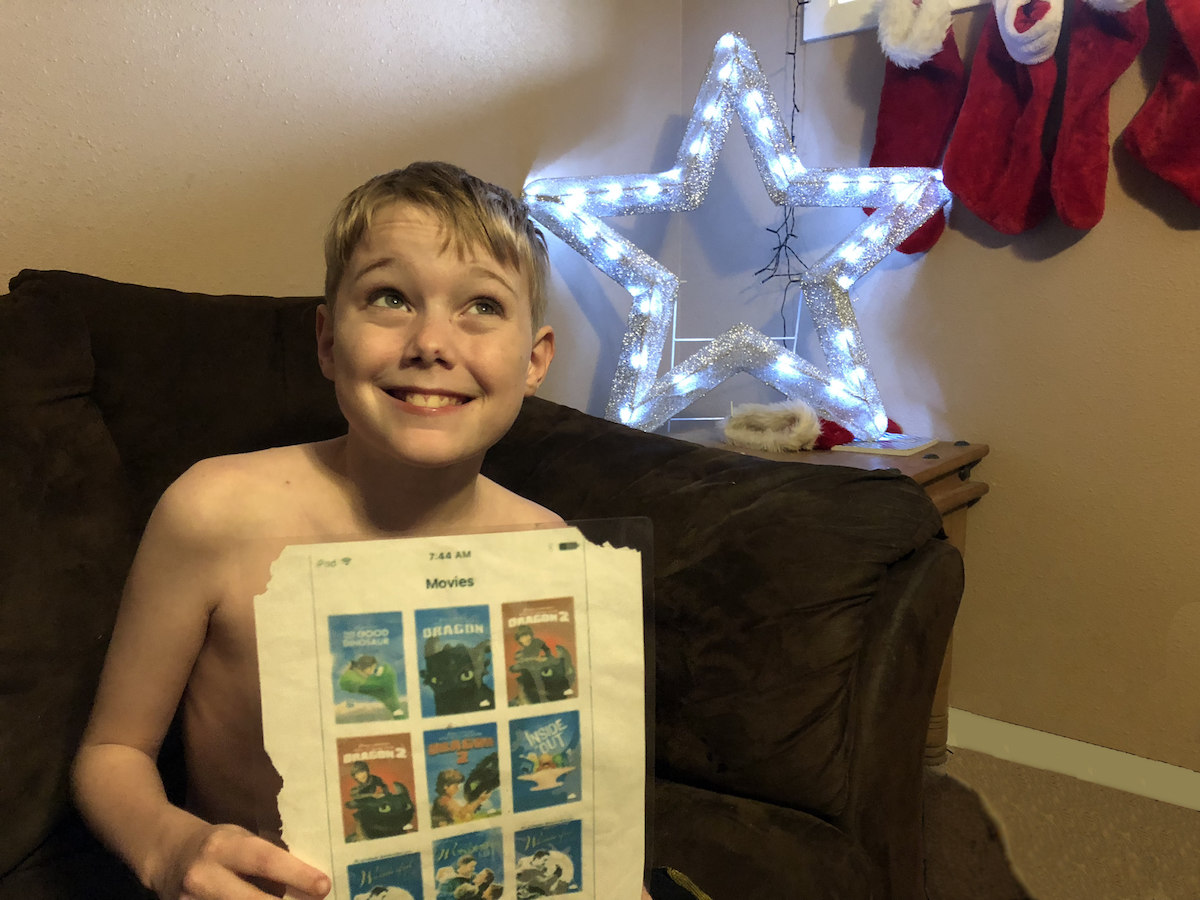

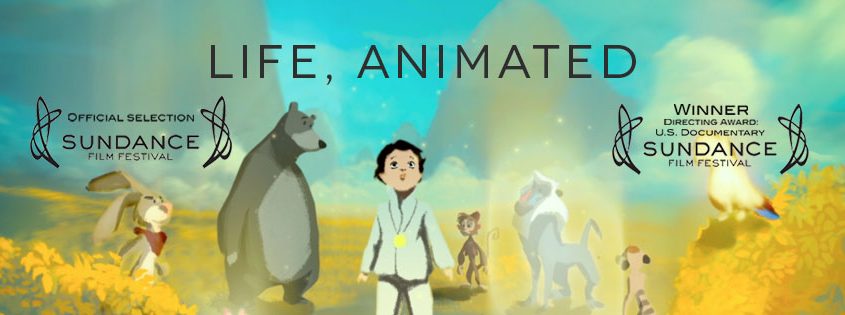

to take the scissors away for safety’s sake. But then I saw what you were working on. Your blade got close to the movie covers. Very close. You trimmed around each of them until you had eight perfect little rectangles. And that’s when I realized it. You were disassembling your digital movie shelves and reassembling them in a new order–one that you picked yourself.

to take the scissors away for safety’s sake. But then I saw what you were working on. Your blade got close to the movie covers. Very close. You trimmed around each of them until you had eight perfect little rectangles. And that’s when I realized it. You were disassembling your digital movie shelves and reassembling them in a new order–one that you picked yourself.

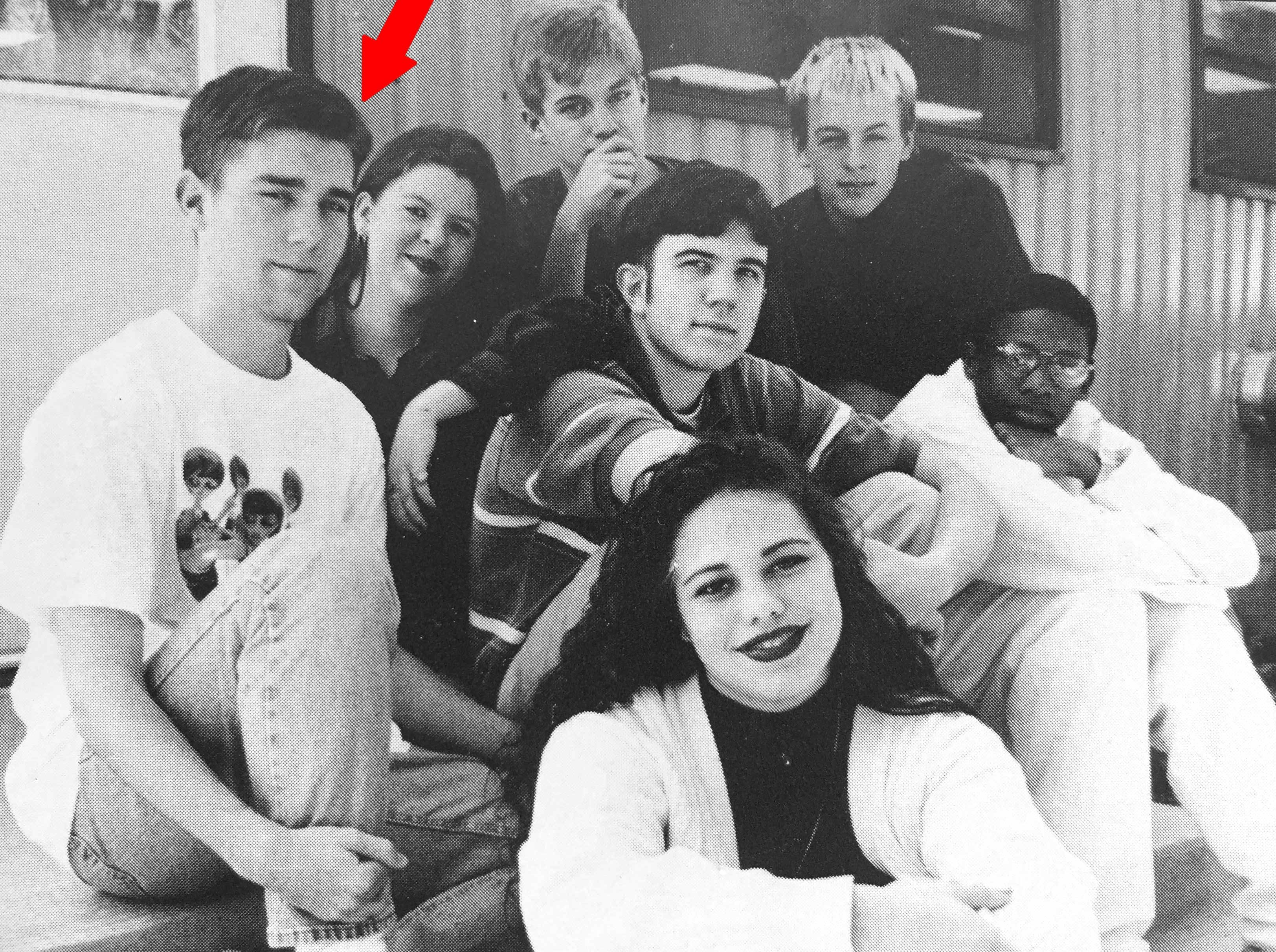

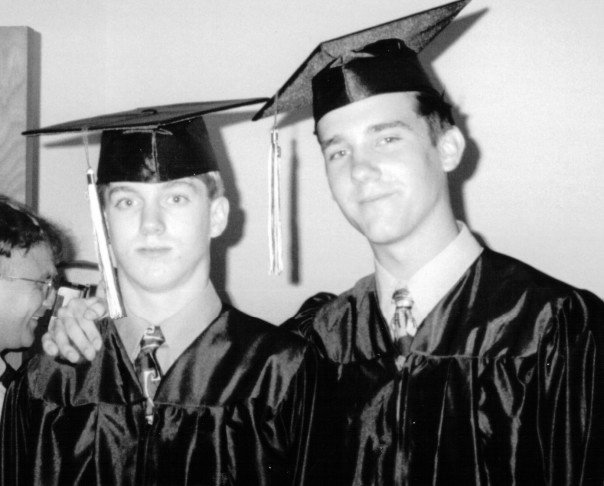

Seventeen years from now, something small will happen. You’re going to develop a nickel allergy, making you allergic to your wedding ring. So you’ll go without one for a few years. Then, out of the blue, a man will hear you preach, and he’ll offer to make you a new one that you can actually wear. But instead of gold, he’ll inlay it with redwood.

Seventeen years from now, something small will happen. You’re going to develop a nickel allergy, making you allergic to your wedding ring. So you’ll go without one for a few years. Then, out of the blue, a man will hear you preach, and he’ll offer to make you a new one that you can actually wear. But instead of gold, he’ll inlay it with redwood. A shout out to my friend Dan of the 511 Workshop. He’s the artist who made my new wedding ring. He does phenomenal, custom work. Check out his

A shout out to my friend Dan of the 511 Workshop. He’s the artist who made my new wedding ring. He does phenomenal, custom work. Check out his

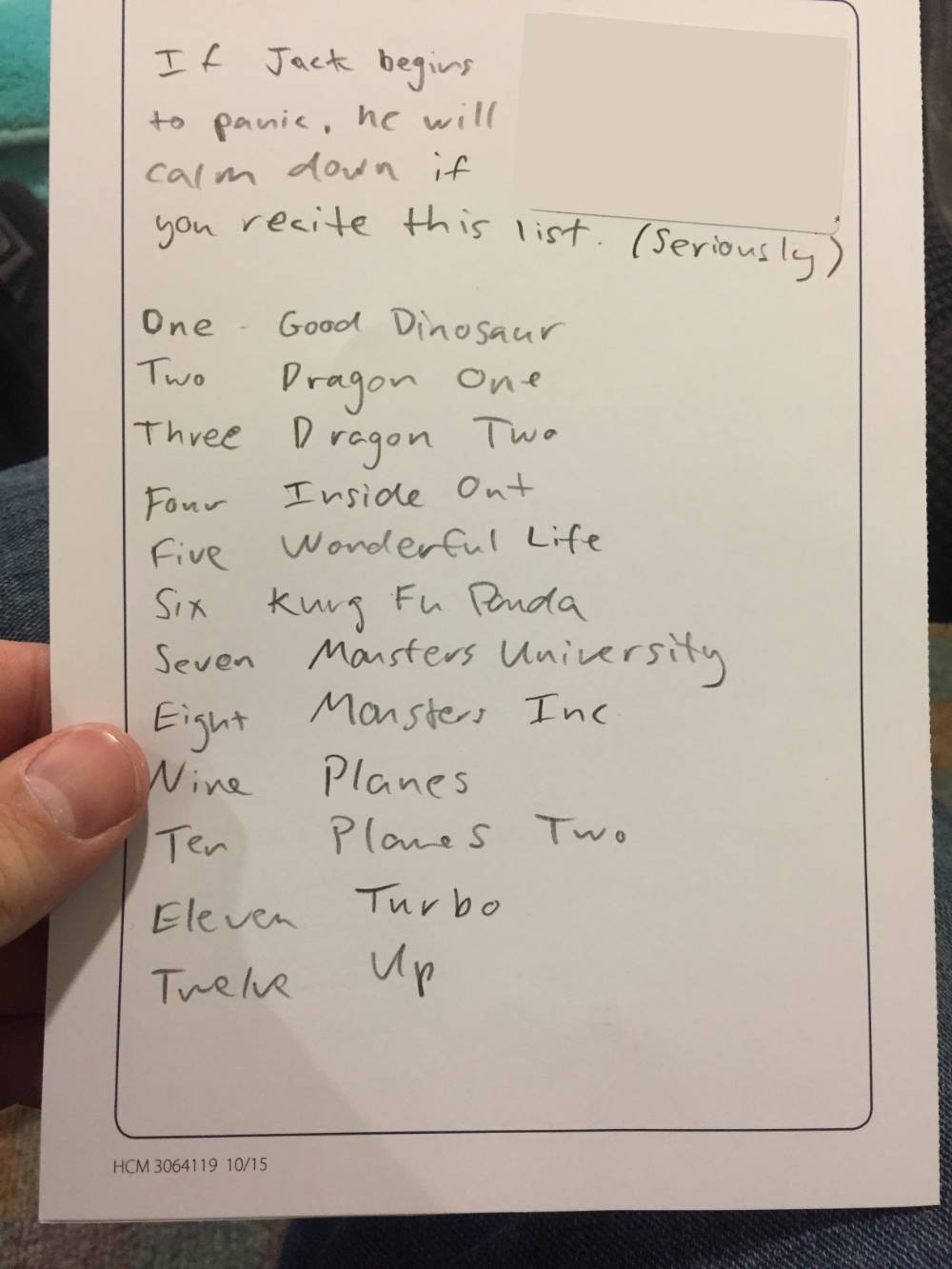

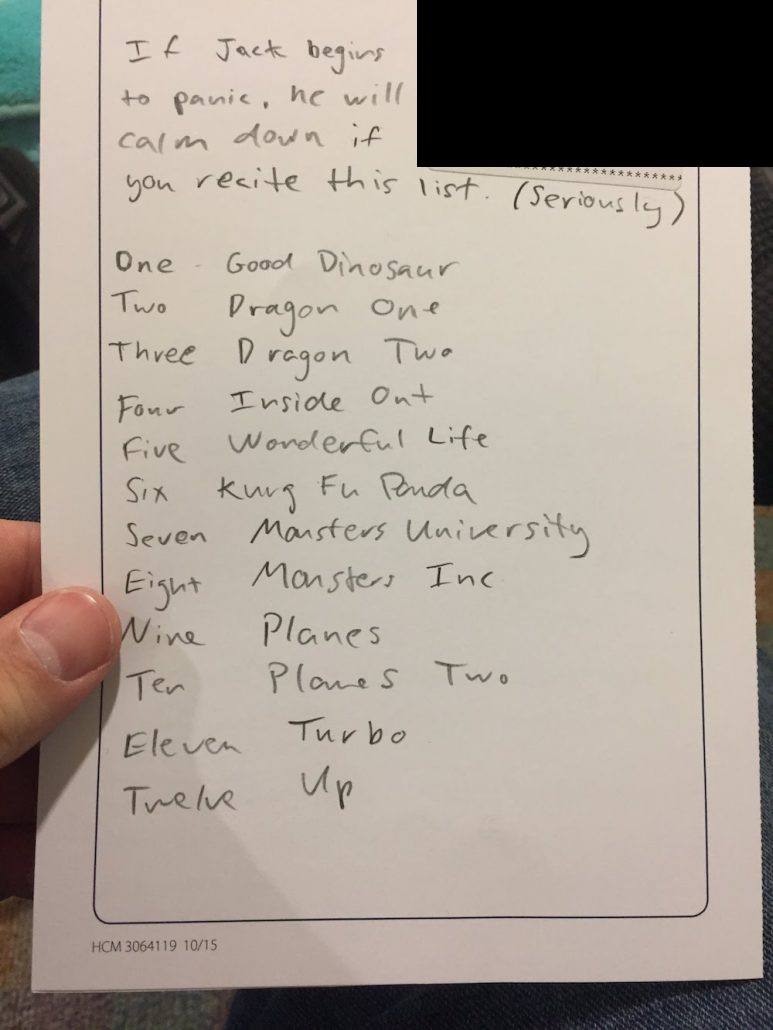

Things turned around a bit in May, but he’s taken a dip again since Apple auto-updated some of their iTunes movie covers two days ago. The Good Dinosaur picture is different. It’s just Arlo now. Spot is gone, and Jack’s head is exploding.

Things turned around a bit in May, but he’s taken a dip again since Apple auto-updated some of their iTunes movie covers two days ago. The Good Dinosaur picture is different. It’s just Arlo now. Spot is gone, and Jack’s head is exploding.