The Porcelain Light of Promise

We need to talk about those screenshots.

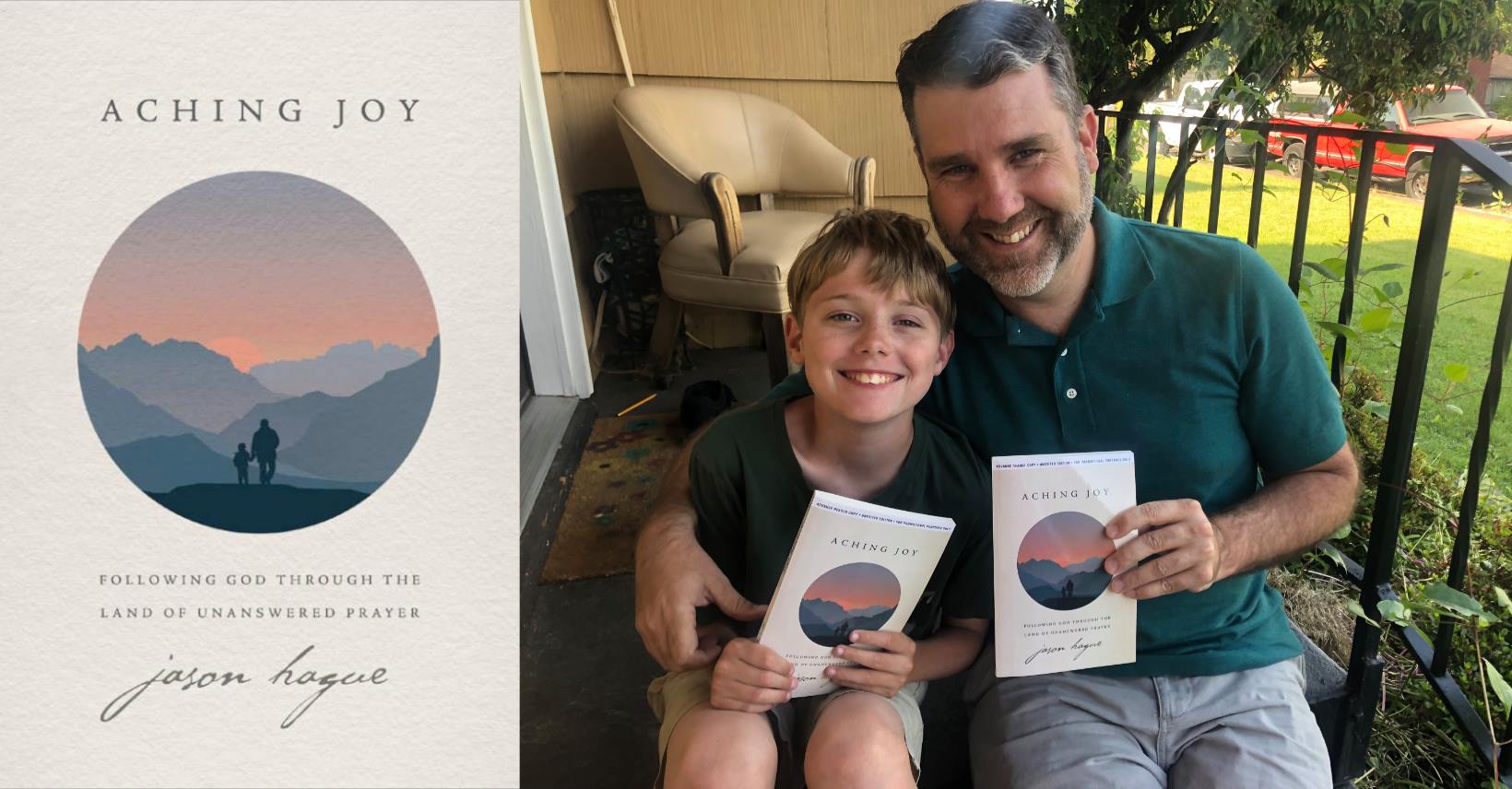

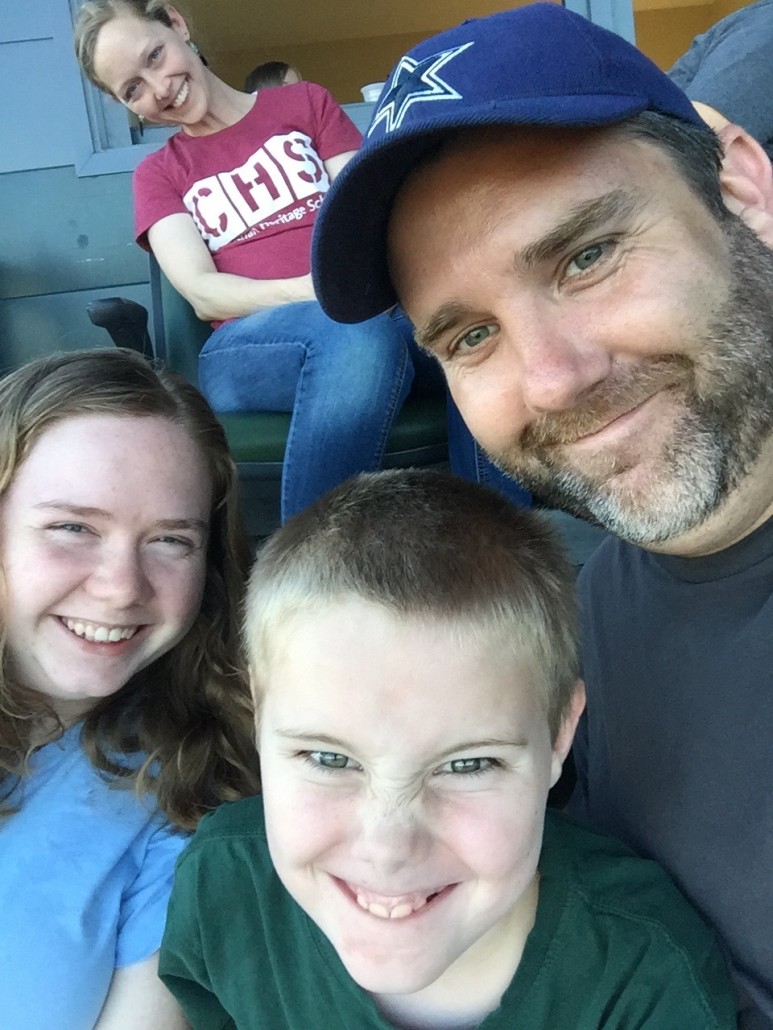

When Jack started texting me a couple months ago, I was ecstatic. He has autism, you see, and at fifteen years old, he still doesn’t really speak. We communicate, but we never converse. And I’ve always wanted to converse.

Then, all of a sudden, there he was telling me he liked my Winnie the Pooh voices, and that he liked when we held hands (something that reminded me of the very first communication breakthrough we ever had.) Back and forth we went, trading Gru gifs and Despicable Me quotes. It was (dare I say it?) a real conversation.

I shared the moment with all of you, and the result was predictably awesome. Congratulatory messages poured in on the internet. Over on Twitter, the screenshot went viral. At its peak, the tweet was earning a thousand new likes every ten minutes.

Truly, it should have been a triumphant weekend. But in the middle of the cheers, I felt a nagging itch to rush in and throw cold water on everyone; to say it wasn’t that big a deal. After all, Jack had been using his device to answer questions in school and spell words for months. This wasn’t, like, a miracle. I mean yes, it was cool, and promising, but only a little promising.

Why did I feel the urge to downplay something so significant? Because in my experience, good news is a fragile thing. Promise is porcelain, best if packed in bubble wrap and tissue paper. It wasn’t you I wanted to protect. It was me.

Two weeks ago, I sat with my spiritual director in his home on the MacKenzie River. I told him how I never think about the future. That it’s a place I don’t go anymore. I used to be a sentimental dreamer back before my heart broke over my son. My heart isn’t broken anymore, but I still don’t dream. And sometimes, I want it back—the ability to imagine what better days might look like. I miss it.

So that afternoon, I closed my eyes and I did something new. I went there. I imagined what the future might look like Jack, who turns sixteen in just six short weeks. I visualized the scenarios that parents in my position know all too well: he lives with Sara and me until we die; he lives with his siblings (but dear God, they’ve given so much already); he lives apart from all of us in a group home.

These were vague, shadowy images, because I didn’t want to get too close, or move too quickly. I felt like I was crossing a frozen lake.

And then, just when I was ready to open my eyes and return safely to the present, I asked myself a terrifying question: What if? As in… What if something better happened?

What if this new texting breakthrough was a real breakthrough?

What if Jack fell in love with this type of communication?

What if it became habitual?

What if he used his device to tell us all the things in his heart?

What if he showed other people, too?

What if he made friends? Real friends?

What if he fell in love with the satisfaction of being known?

What if he got a job? The kind of job that helped him make sense of the world, and feel good about himself?

When I opened my eyes, my face was wet, and my stomach was churning. I thought I might be sick.

The truth is, I feel pretty well prepared for the harder scenarios. I’m ready for a life of minimal communication with my son. We’ve lived this way for a long time, and I promise you, we are plenty happy. Jack loves his family, and he loves me. We wrestle and we laugh, we shadow box in the kitchen, and we stomp out the rhythms to our favorite songs. We have a beautiful relationship. My boy is enough for me. Right now. Like this. Today. He is enough.

I’m not afraid of a long, dark road. No, it’s the brightness that haunts me; the porcelain light of promise. Because I have seen how easily hope shatters. I saw it happen too many times in the early days, and I thought I had recovered. But I hadn’t. My stomach remembered. It reminds me even now, while I write these words.

Two more weeks have passed, and we sit in our church sanctuary, waiting for the recital to begin.

“Are you ready for this, bud?” I ask. Jack tilts his head, squints his eyes, and stares at the wall. This boy hates being watched, and he’s never done anything on a stage. We’re not sure if he’ll play today. I’m skeptical. Always skeptical.

But when Miss Debbra calls his name, he grabs his book and stands up. My friends across the aisle pick up their phones and ready their cameras. They know what this moment means.

Sara climbs the stairs with Jack and takes him to the keyboard. He pounds on the keys before getting situated. Just testing them. Then, he takes his seat, and in front of all those other kids and their families, he Decks the Halls with Boughs of Freaking Holly.

My friend are all texting me. ”The front row isn’t crying over here,” they lie.

And amid the cheering, I am reminded how much we all need hope in our lives. We can live without it, I suppose, if by “live” we mean “passing time on a spinning globe.” We can stare down on our feet and ignore the inevitabilities waiting at the horizon. But that is more loitering than living. I want to do something better. I want to lift my eyes; to watch for the sunset, with its dazzling blend of color and cloud. Because beauty awaits those who are brave enough to believe.

I’m getting there. I’m choosing not to downplay Jack’s progress. He is texting us. He is making jokes, and telling us things like, “I like it when I’m funny.” And he’s walking over to the piano, hammering out little riffs he’s heard on his favorite movies. This is beauty. This is growth. And even if it all shatters in another regression, I will come back here and preach this same sermon to myself, like I have so many times before:

Hope is good.

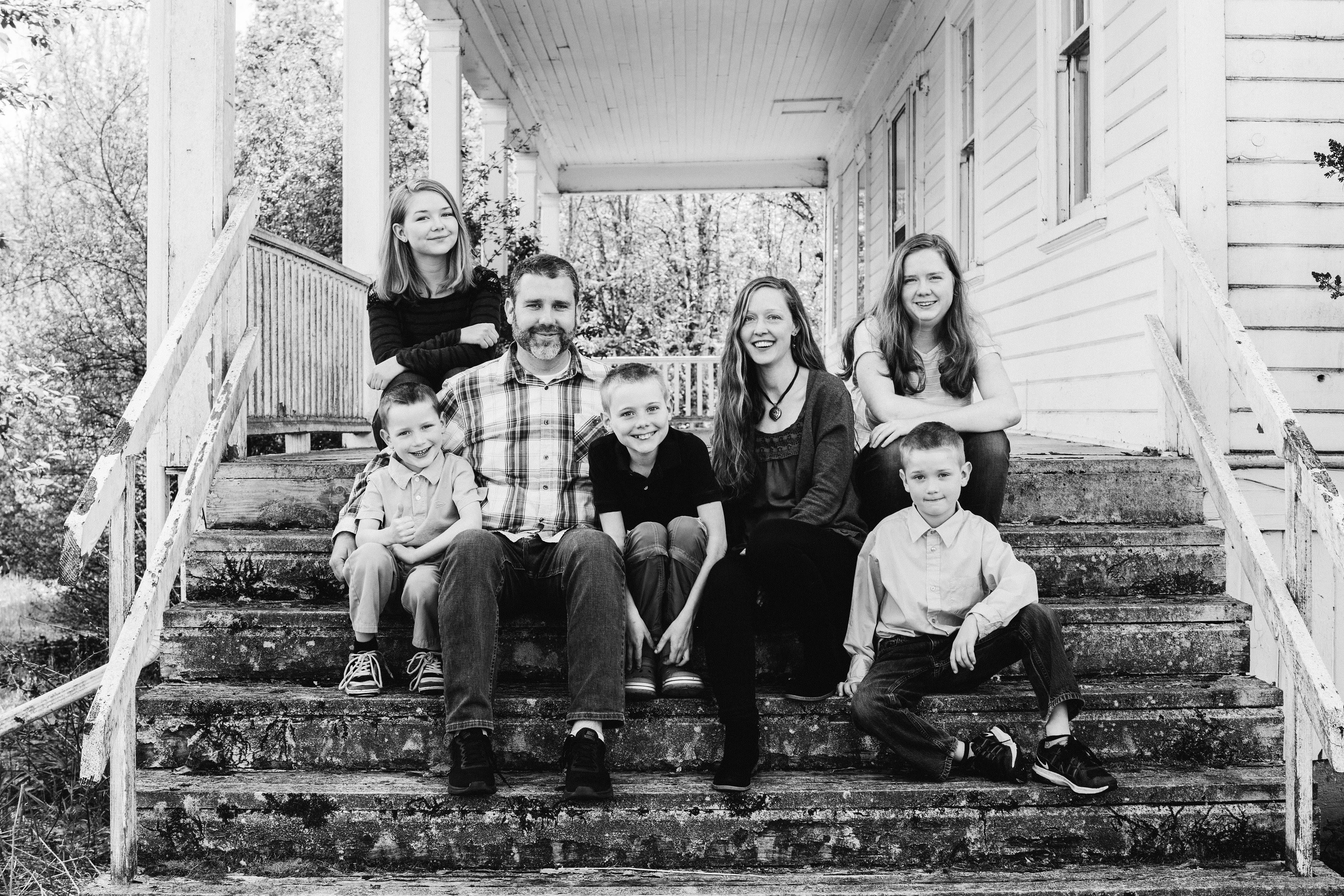

Many things in your world are changing. Your big sister just turned eighteen, for one thing. Soon, she will go to college, and she will leave her bedroom. We won’t see her as often because she will be making a new life with studies and friends, and I imagine she’ll even have her own family someday. You will miss her. We all will. But it will be a good kind of pain.

Many things in your world are changing. Your big sister just turned eighteen, for one thing. Soon, she will go to college, and she will leave her bedroom. We won’t see her as often because she will be making a new life with studies and friends, and I imagine she’ll even have her own family someday. You will miss her. We all will. But it will be a good kind of pain.

Today, Kyle is sixteen years old, and he is a paid member of our church staff. He worked himself into a job. He has grown into a kind, hard-working young man, and is a true asset to our team. The guy just gets stuff done, and we love having him around.

Today, Kyle is sixteen years old, and he is a paid member of our church staff. He worked himself into a job. He has grown into a kind, hard-working young man, and is a true asset to our team. The guy just gets stuff done, and we love having him around.

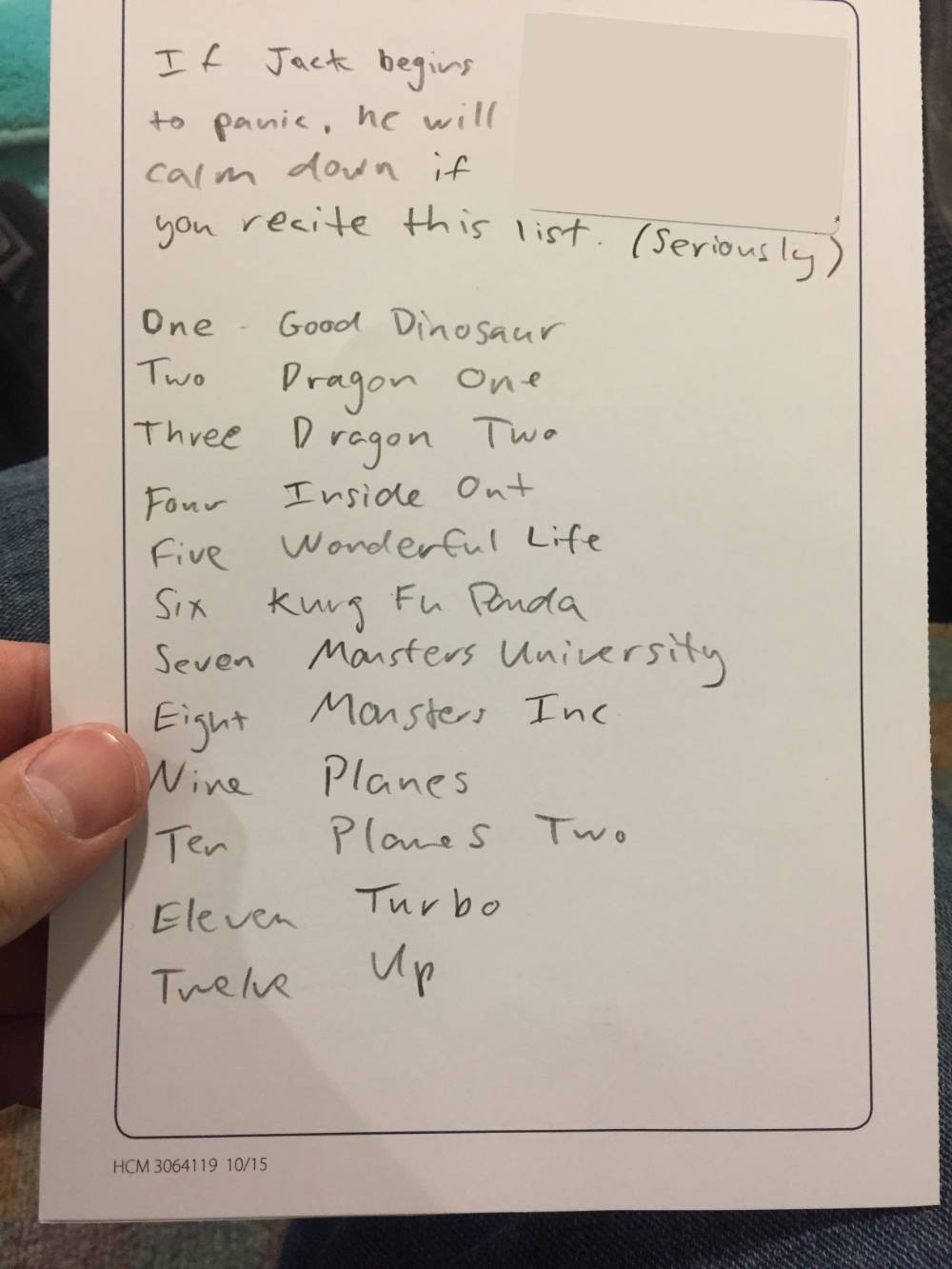

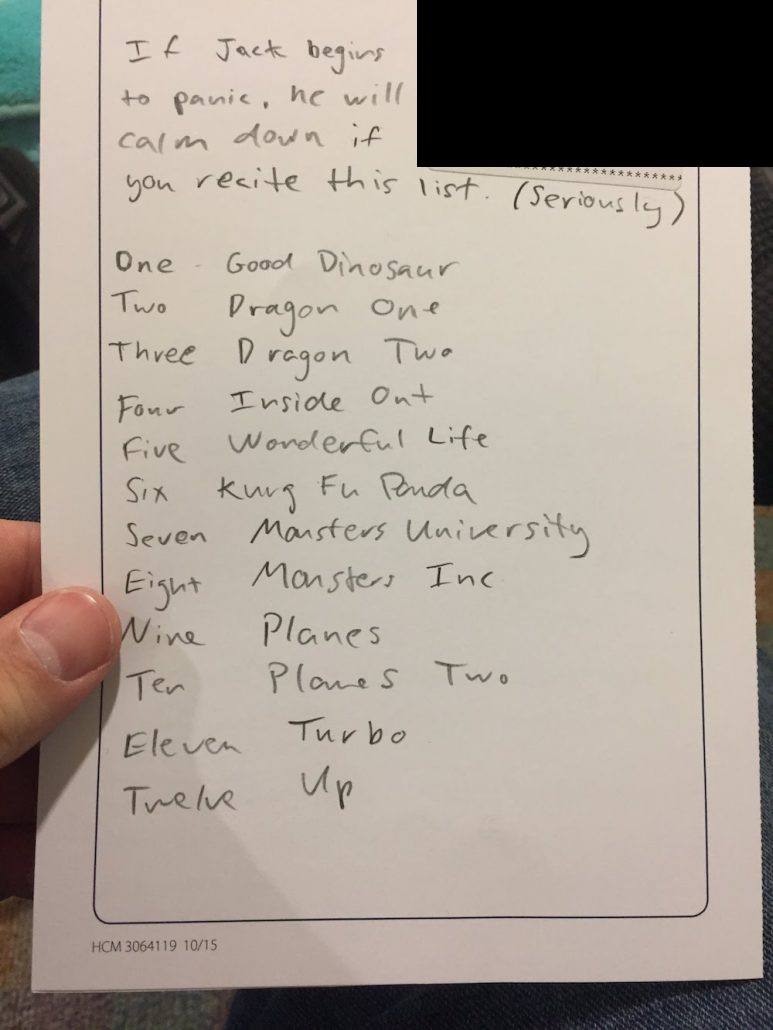

Things turned around a bit in May, but he’s taken a dip again since Apple auto-updated some of their iTunes movie covers two days ago. The Good Dinosaur picture is different. It’s just Arlo now. Spot is gone, and Jack’s head is exploding.

Things turned around a bit in May, but he’s taken a dip again since Apple auto-updated some of their iTunes movie covers two days ago. The Good Dinosaur picture is different. It’s just Arlo now. Spot is gone, and Jack’s head is exploding.

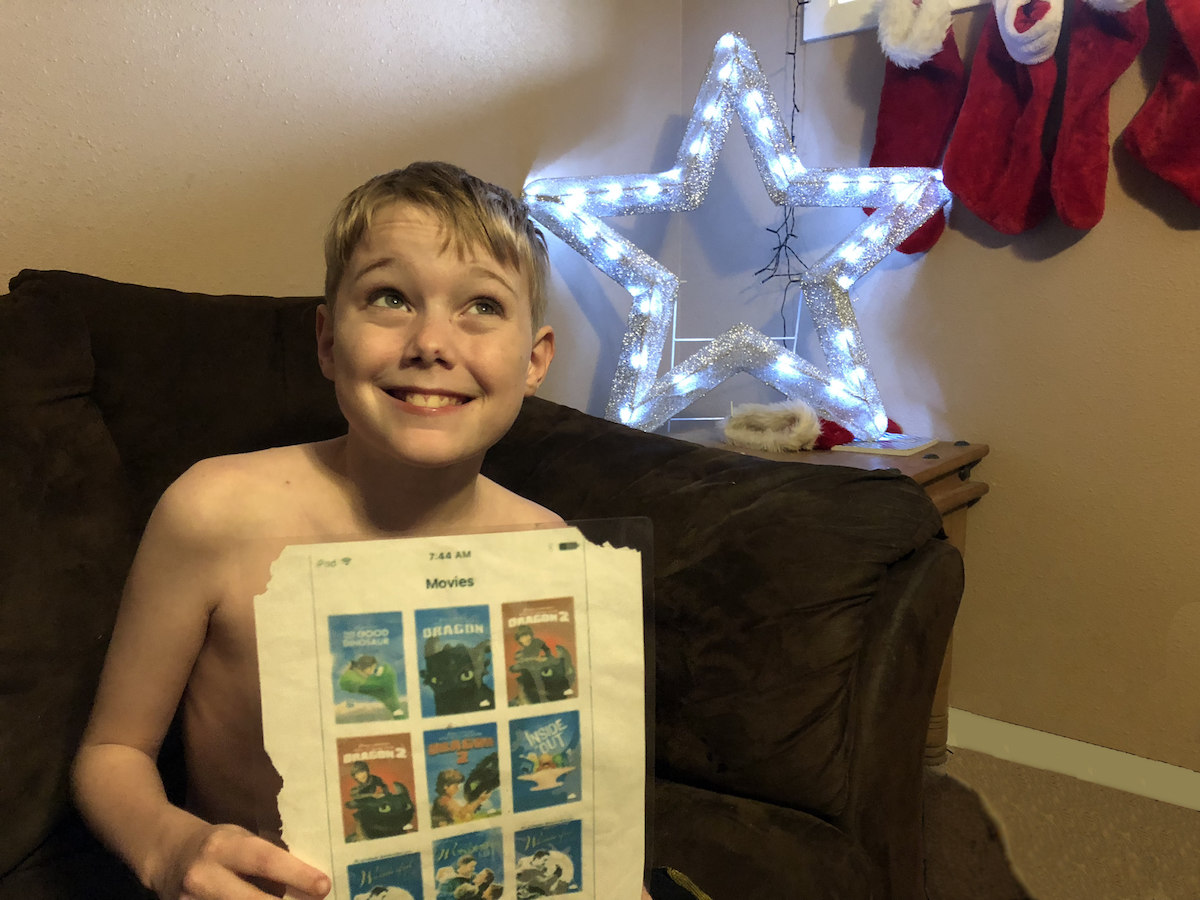

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out:

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out: