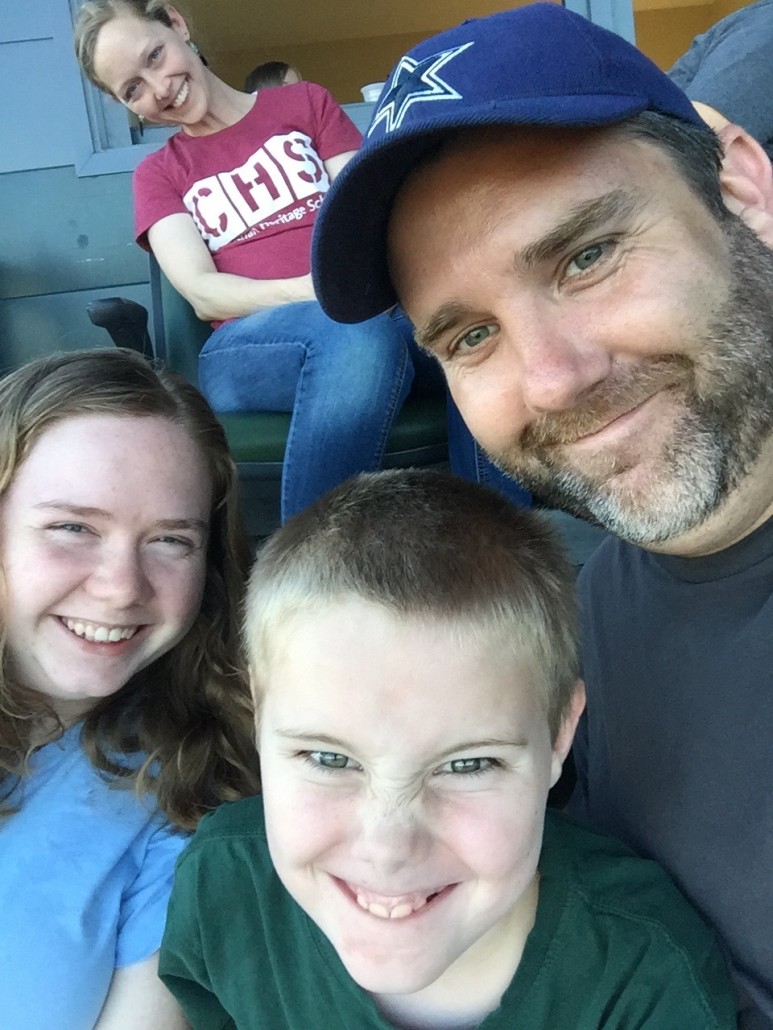

A Letter to My Autistic Son on his 16th Birthday

Dear Jack,

All birthdays are special, but some are more special than others. The sixteenth birthday is one of the very best ones, because when you turn sixteen, you’re almost done being a kid. And on days like this, a lot of people start to think more about what they might be able to give to the world in order to make it a better place.

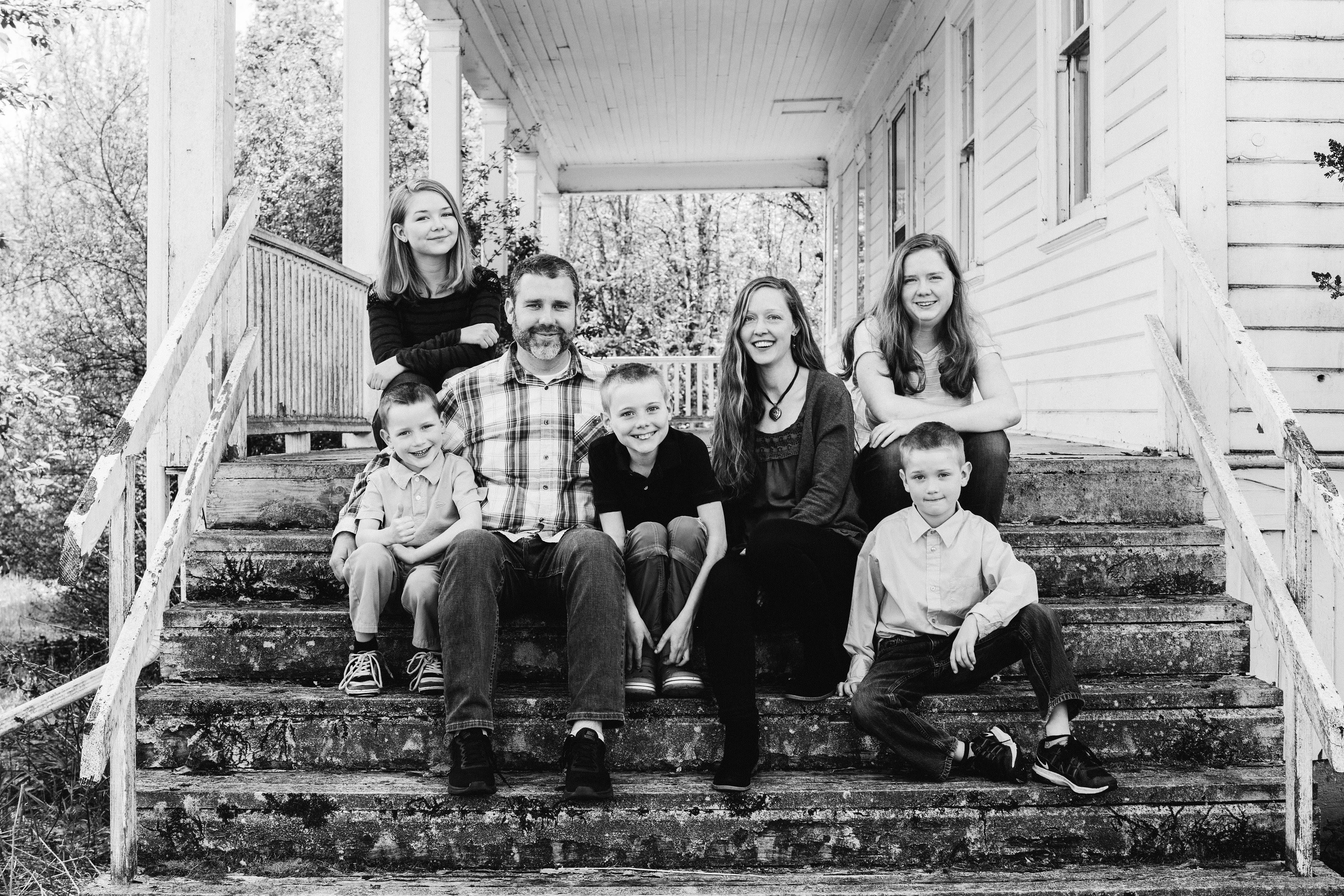

I know you see these things in your siblings: Nathan singing and dancing on stage; Sam making everyone laugh with his impressions; Jenna creating amazing artwork; Emily making beautiful things out of words. These are all gifts, kind of like in Encanto.

Son, you don’t talk very much, but you have gifts, too. Maybe you think you’re like Mirabel in the movie, who didn’t get one. But Mirabel was wrong, because she did have gifts. She had the gift of seeing and understanding other people. That’s how she was able to bring healing to her family. Some gifts aren’t as obvious as others.

You have some obvious gifts that everyone sees. You have joy, for one thing. People see you skipping through the hallways on Sunday mornings with Leeli on her leash, and they smile, because you’re smiling. Your joy spreads.

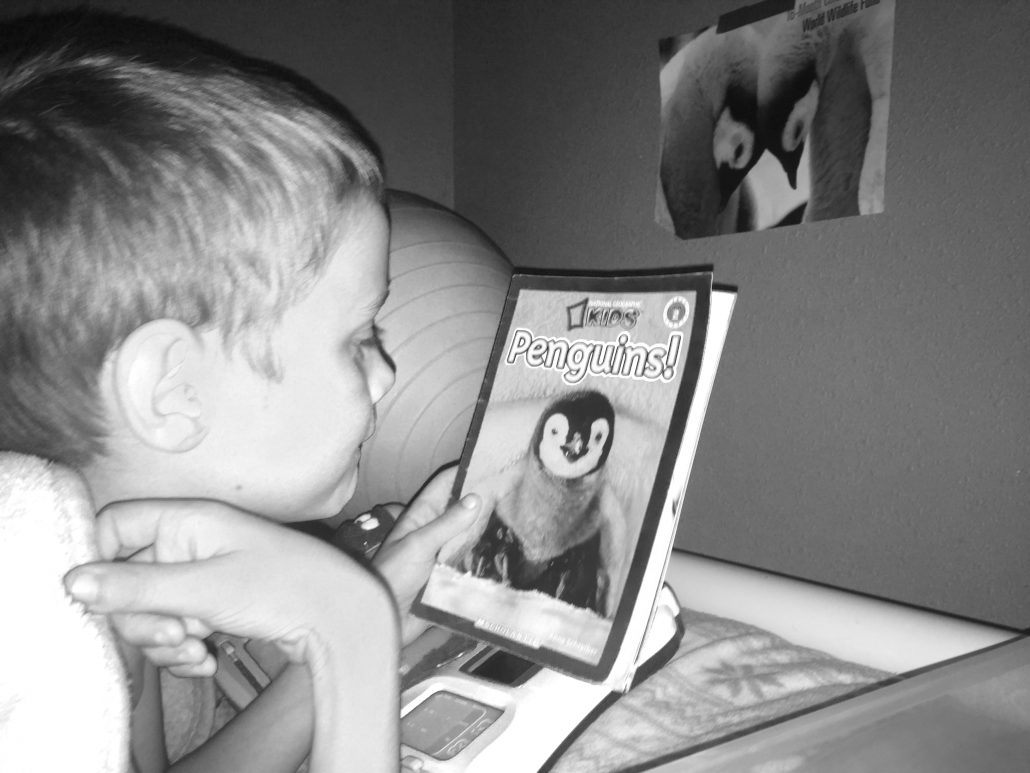

But there’s something else, son—a surprising gift that we’re starting to see from you, and we want you to see it, too: Jackson, you are a storyteller.

Let me tell you why I think this is true. Stories are not just about the characters in the book or on the screen. No, they are really about how those characters connect with us, the people who are watching and reading. They wake up the sleepy parts of our hearts. You seem to understand this in a very special way.

Let me give you an example. Remember a few weeks ago when we were texting about Kung Fu Panda? You said to me, “You are Monkey because you are funny and I am Po because I am kind.”

This made me very happy for two reasons. First, you understood that you are kind. You see that in yourself, and that is a wonderful thing. It’s another of your gifts, just like joy. But you also recognized what the movie is really about. It’s not just about Po learning Kung Fu. It’s about how he had a good heart, even when nobody believed in him.

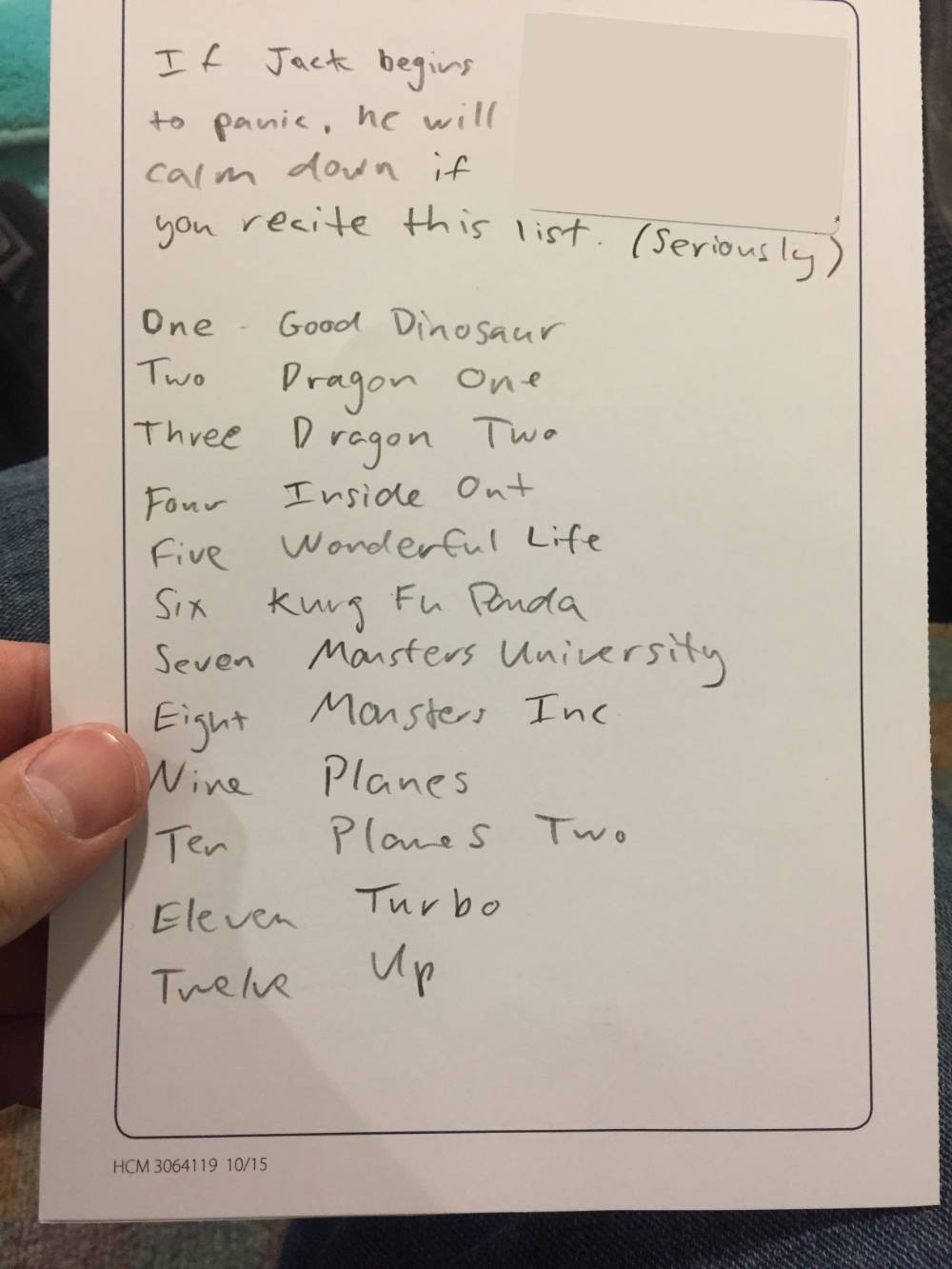

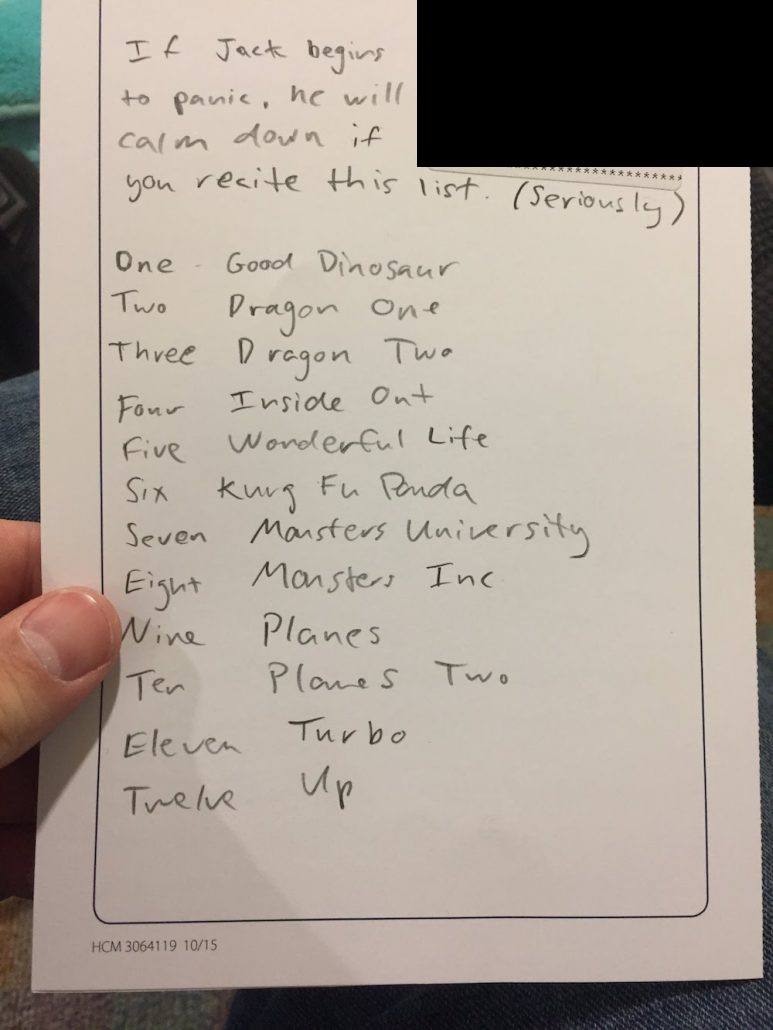

Do you see what I mean? Stories are about connection. The more I think about this idea, the more I suspect you’ve always understood it. Like when you related to The Good Dinosaur’s constant anxiety, or when you saw yourself in Mater, not just because he was awkward and you felt awkward, but because he was a hero, and you wanted to be one, too.

Yes, I think you’ve always understood stories. That should be no surprise, because we are a story family. It’s my favorite piece of our little home culture. But I think you can make them, too.

Last month, you were doing school work with mom. Your assignment was to use your communication device to tell us all about your favorite place, and to refer to all five of your senses. Here’s what you told us:

“I like going to the beach. I feel nice because I can feel sun and wind on my face. I like to listen to the waves crash on the shore. I like to watch the waves chase each other across the sand. I can smell fish in the air. I can taste the salt in the air, too. I like going to the beach with my favorite people, my family.”

I read that part about the waves chasing each other, and I shook my head in wonder. This is a poem, son. A story poem. As Hiccup said to Toothless, “You never cease to amaze me, bud.”

Jack, every time you put your thoughts into words like this, you help us connect with you. You bring us into your world so we can know you better. And we love getting to know you better.

You are turning sixteen today, son. You might not be like other adults-in-training, with all their talking and driving and thinking about college. That’s okay with us. But please believe me when I say that you have special gifts to give to the world. We need your joy. We need your kindness. And we need your deep and surprising sense of connection.

Mom and I love you, son. And we are so proud of the story you’ve begun to write. Happy 16th birthday.

Dad

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out:

(Ed’s Note — I think this guy deserves a special shout out:

“1 in 50.”

“1 in 50.”